The Universe's Wild Ride - An 8-Threshold Cosmic Chronicle!

Hey space-time travelers! Ever wondered how we got from a universe smaller than an atom to... well, all this? Our story is a sprawling epic, beginning with the very dawn of space and time, winding through the fiery birth of stars, the alchemical forging of elements, the quiet cradle of planets, the audacious spark of life, the head-scratching rise of intelligence, the hustle and bustle of civilization, and the warp-speed sprint to modern times. Phew! It's a vast and complex tale, alright! But fear not, intrepid explorer! We can chart this incredible journey by breaking it down into eight key thresholds of increasing complexity. Each threshold represents a moment when the universe leveled up, creating something entirely new and more intricate than before.

Ready to time-travel? Let's hit these cosmic milestones:

- Creation: The Big Bang – Where It All Began!

- Star Power: The Birth and Blazing Lives of Stars

- Cosmic Kitchens: How Stars Cooked Up the Elements

- Worlds in the Making: Planets – The Cradles of Possibility

- The Spark: Life's Grand Entrance on Earth

- Thinking Big: The Dawn of Human Intelligence

- Building Blocks of Society: Agriculture & The Rise of Civilizations

- Full Throttle: The Fast Lane to Modernity

Let's dive in!

Threshold 1: Creation – The Big Bang & Cosmogony

Our first threshold is the ultimate origin story – the very beginning of our Universe. We're talking about the Big Bang, the cataclysmic event that kicked off space, time, and everything within them. Forget what you think you know about explosions; this was something else entirely!

In those first, almost unimaginably tiny fractions of a second, the Universe was a seething, hyper-dense, super-hot soup of pure energy. As it began to expand and cool at a mind-boggling rate (and we mean really mind-boggling!), the fundamental forces of nature started to peel apart, and the very first particles blinked into existence. This early period set the stage, through a series of dramatic epochs, for the grand cosmic structure we see around us today.

Key Concepts: The Universe's Baby Pictures & First Steps

Let's unpack some of the mind-bending ideas that describe this primordial era:

Planck Scale: Where Physics Goes "Huh?" This is the teeniest, tiniest scale imaginable, beyond which our current rulebook of physics (even quantum mechanics and general relativity as we know them) might just throw up its hands and say, "I got nothing!" It's where quantum effects of gravity are thought to rule.

Think of Planck Time as the very first "tick" of the cosmic clock we can even begin to theorize about.

Quantum Fluctuations: The Universe's First Jitters Imagine empty space not being truly empty, but fizzing with tiny, temporary bursts of energy. These are quantum fluctuations, a fundamental quirk of quantum mechanics predicted by the uncertainty principle. Some theories suggest these tiny jitters could have been the seeds for... well, everything!

Vacuum State: Not So Empty After All! In quantum field theory, a vacuum isn't just nothingness. It's the lowest energy state of a field. But "lowest" doesn't always mean "zero"! If a vacuum state has a non-zero energy density, general relativity tells us it acts like a repulsive force, pushing space apart. This idea is crucial for...

Singularity: The Ultimate "Before"? This is a point (or state) where things like density and spacetime curvature theoretically become infinite, and our known laws of physics just break down. The Big Bang is often described as originating from such a gravitational singularity. What caused it? Maybe a previous universe collapsing, or perhaps those wild quantum fluctuations of the vacuum!

Grand Unified Theory (GUT): When Forces Were One Way back in the super-early, super-hot Universe, the fundamental forces we see today (electromagnetism, weak nuclear force, strong nuclear force) might not have been distinct. GUTs propose they were all merged into a single, unified force. As the Universe cooled, this symmetry "broke," and the forces went their separate ways.

Cosmic Inflation: The Universe's Biggest Growth Spurt! Just a tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang (around to seconds!), the Universe is thought to have undergone an absolutely insane period of exponential expansion. Driven by a high-energy vacuum state, it ballooned from subatomic size to something perhaps grapefruit-sized (or vastly larger!) almost instantaneously. This isn't your everyday expansion; this was hyper-expansion! Inflation brilliantly explains why the Universe is so incredibly large, flat, and uniform (homogeneous and isotropic) on cosmic scales. Those tiny quantum fluctuations we mentioned? Inflation would have stretched them to enormous sizes, creating the slight density variations that later seeded the formation of galaxies!

(Image: A timeline showing cosmic inflation, the formation of the CMB, and the subsequent evolution of the Universe.)

(Image: A timeline showing cosmic inflation, the formation of the CMB, and the subsequent evolution of the Universe.)

Sakharov Conditions: Why Is There Stuff, Not Just Light? Ever wonder why there's more matter than antimatter in the Universe? If they were created in equal amounts, they should have annihilated each other, leaving just a sea of photons! Andrei Sakharov laid out three conditions necessary for this imbalance (baryogenesis) to occur:

- Baryon number violation: Processes that don't conserve the number of baryons (like protons and neutrons).

- C and CP violation: Charge conjugation (C) and Charge-Parity (CP) symmetries must be violated – meaning matter and antimatter (and their mirror images) don't behave exactly the same.

- Departure from thermal equilibrium: The reactions creating the imbalance must happen when things aren't settled and uniform.

Cosmic Neutrino Background (CB): Ghostly Relics About one second after the Big Bang, the Universe became transparent to neutrinos. These super-shy, weakly interacting particles decoupled from the rest of the matter and have been streaming freely through the cosmos ever since, forming a background much like the more famous CMB. Detecting them is incredibly hard, but they're a crucial piece of the Big Bang puzzle.

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN): The First Elements Are Cooked! Between a few seconds and about 20 minutes after the Big Bang, the Universe was hot and dense enough to be a cosmic nuclear furnace. Protons and neutrons fused to form the nuclei of the lightest elements: mostly hydrogen (about 75%) and helium-4 (about 25%), with tiny traces of deuterium (H-2), helium-3, and lithium-7. The abundances of these light elements predicted by BBN match observations remarkably well – a major triumph for the Big Bang theory!

(Image: Reaction pathways during Big Bang Nucleosynthesis, showing the formation of light elements.)

(Image: Reaction pathways during Big Bang Nucleosynthesis, showing the formation of light elements.)

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB): The Universe's Baby Picture! For about 370,000 years, the Universe was a hot, opaque plasma of nuclei, electrons, and photons. Photons couldn't travel far without bumping into charged particles. But as the Universe expanded and cooled to about 3000 K, electrons and nuclei could finally combine to form neutral atoms (mostly hydrogen and helium) – an event called recombination. Suddenly, photons were free to travel unimpeded! This ancient light, released when the Universe became transparent, is what we now detect as the Cosmic Microwave Background. Due to the Universe's expansion, this light has been redshifted all the way from the visible/infrared spectrum down to microwaves. The CMB is an incredibly uniform glow across the entire sky, but it has tiny temperature fluctuations (anisotropies) – those seeds of structure magnified by inflation!

(Image: The CMB as observed by WMAP, showing tiny temperature fluctuations.)

(Image: The CMB as observed by WMAP, showing tiny temperature fluctuations.)

Hubble's Law: The Expanding Canvas Edwin Hubble's observations in the 1920s showed that distant galaxies are moving away from us, and the farther away they are, the faster they recede. This is the hallmark of an expanding Universe. Where is the recessional velocity, is the distance, and is the Hubble constant – a measure of the current expansion rate.

Cosmological Principle & FLRW Metric: The Universe's Geometry On very large scales, the Universe appears to be homogeneous (the same everywhere) and isotropic (the same in all directions). This is the Cosmological Principle. It's the foundation for the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric, which describes the geometry of such a universe within Einstein's General Relativity: Here, is the crucial scale factor, telling us how distances stretch as the Universe expands, describes the overall curvature (flat , spherical , or hyperbolic ), and .

Friedmann Equations: The Universe's Dynamics Derived from General Relativity using the FLRW metric, these equations govern the expansion of the Universe, relating it to its energy density (), pressure, curvature (), and the cosmological constant (): (Note: Often in cosmology units. includes matter, radiation, and dark energy.)

CDM Model: The Standard Recipe for the Cosmos This is our current "standard model" of cosmology. It combines the Big Bang theory with:

- (Lambda): Representing dark energy, a mysterious component causing the Universe's expansion to accelerate.

- CDM: Cold Dark Matter, an invisible form of matter that interacts gravitationally but not electromagnetically.

The recipe is roughly:

- 68.3% Dark Energy

- 26.8% Dark Matter

- 4.9% Ordinary Matter (the stuff we see: atoms, stars, galaxies!)

(Image: Pie chart showing the energy density composition of the Universe according to the CDM model.)

(Image: Pie chart showing the energy density composition of the Universe according to the CDM model.)

Dark Matter: The Invisible Scaffolding We can't see it, but dark matter's gravitational pull is essential for explaining how galaxies rotate, how they cluster together, and how large-scale structures formed in the Universe. It's like an invisible cosmic web providing the scaffolding.

Dark Energy: The Cosmic Accelerator Observations of distant supernovae in the late 1990s revealed a shocker: the Universe's expansion isn't slowing down due to gravity as expected; it's accelerating! Dark energy is the name we give to whatever is causing this cosmic push. Its nature is one of the biggest mysteries in physics.

Perturbation Theory: From Smooth to Lumpy If the early Universe was almost perfectly smooth, how did we get galaxies and clusters? Tiny quantum fluctuations, amplified by inflation, created slight density variations. Perturbation theory is the mathematical tool cosmologists use to study how these small initial "lumps" grew over billions of years due to gravity, eventually collapsing to form all the structures we see.

Jeans Instability: When Gravity Wins In a cloud of gas, gravity wants to pull it together, while pressure wants to push it apart. The Jeans instability occurs when a region of a fluid becomes dense enough (or cool enough) that gravity overcomes pressure support, causing it to collapse and form structures like stars and galaxies. The critical size for this collapse is the Jeans length (): (The first form uses sound speed , the second, Boltzmann constant , temperature , mean molecular weight , hydrogen mass , and density .)

Epochs: A Quick Tour Through the First Moments

The early Universe went through several distinct phases or "epochs" – talk about a wild ride!

| Epoch | Time | Temperature (K) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planck Epoch | s | The "Who knows?" era. Quantum gravity reigns supreme. Our current physics pretty much gives up here! | |

| GUT Epoch | s | Gravity "freezes out" from the other unified forces (the electronuclear or GUT force). Hypothetical X and Y bosons might have allowed matter to flip between quarks and leptons. | |

| Inflationary Epoch | s | KA-BOOM! (But not really an explosion). The Universe expands exponentially by an unimaginable factor, driven by a high-energy vacuum state (the inflaton field). Smooths out the Universe and blows up quantum fluctuations to cosmic scales. The strong force separates from the electroweak force at the end of this or start of next. | |

| Electroweak Epoch | s | Temperature still incredibly high. Strong force is distinct, but electromagnetic and weak forces are still unified as the "electroweak" force. Exotic particles abound. W and Z bosons are created but are massless as the Higgs field's vacuum expectation value is zero. Photons don't "exist" in their familiar form yet. | |

| Quark Epoch | s | Universe cools enough for electroweak symmetry to break. W and Z bosons get mass (thanks, Higgs field!), and the weak force becomes short-range. Fundamental interactions get their modern forms. It's still too hot for quarks to bind into protons/neutrons; they roam free in a quark-gluon plasma. Baryogenesis (matter-antimatter asymmetry) might occur here. Photons are now present. | |

| Hadron Epoch | s | Cool enough for quarks to bind into hadrons (protons, neutrons, mesons). Hadron/anti-hadron pairs are created and annihilate. A slight excess of hadrons over anti-hadrons (from baryogenesis) remains. Protons and neutrons interconvert rapidly via weak interactions. Neutron:proton ratio starts to shift from 1:1 due to neutron's slightly higher mass. | |

| Lepton Epoch | s | Most hadrons/anti-hadrons have annihilated. Universe is dominated by leptons (electrons, positrons, neutrinos) and photons. Neutrinos decouple ("freeze out") from matter, forming the Cosmic Neutrino Background. Neutron:proton ratio freezes at about 1:6. Electron-positron pairs are still being created and annihilated. | |

| Nucleosynthesis Epoch | s (20 mins) | Fusion fires up! Protons and neutrons combine to form the nuclei of light elements: primarily Hydrogen (H) and Helium-4 (He-4), with traces of Deuterium (H-2), He-3, Lithium-7. This sets the primordial abundances. Universe is mostly radiation. | |

| Photon Epoch | s years | Universe is a hot, dense, opaque plasma of atomic nuclei, electrons, and photons. Photons are constantly scattering off free electrons. Too hot for neutral atoms to form stably. | |

| Recombination/ Decoupling | years | Temperature drops enough for electrons and nuclei to combine and form neutral atoms (about 500 million H and He atoms per, billion times higher than today). Photons no longer in thermal equilibrium with matter and can travel freely – the Universe becomes transparent! This is when the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation is released. | |

| Dark Ages | No stars yet! The Universe is dark, filled with neutral hydrogen and helium, and the CMB photons redshifting into infrared. The only light is the very faint 21-cm radio waves from neutral hydrogen. Gravity slowly starts to draw matter together in the denser regions. | ||

| Reionization | The first stars and quasars form from collapsing gas clouds. Their intense ultraviolet radiation begins to ionize the neutral hydrogen that fills the Universe, lighting it up again! Dark matter halos play a key role in gathering the baryonic matter. | ||

| Structure Formation | Gravity continues its work, pulling matter into the cosmic web we see today: stars form galaxies, galaxies form groups and clusters, and clusters form superclusters, separated by vast voids. | ||

| Present Day | Here we are! The Universe continues to expand, and that expansion is accelerating due to dark energy. Star formation continues, but at a slower rate than in the past. |

The Far, Far Future: What's Next for the Cosmos?

The Universe won't stay like this forever. Here are some thoughts on its ultimate fate:

- Stelliferous Era (The Starry Era - We're in it!): From first stars until the last stars burn out. Will last for trillions of years.

- Degenerate Era: Only stellar remnants like white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes remain. If protons decay (a hypothetical process), even these will eventually dissolve into leptons and photons over unimaginable timescales ( to years).

- Black Hole Era: If protons don't decay quickly, black holes will be the last organized structures. They too will eventually evaporate via Hawking radiation over even more absurdly long timescales ( years for supermassive black holes!).

- Dark Era: Eventually, only a diffuse bath of photons, neutrinos, electrons, and positrons will remain. The Universe will be cold, dark, and very, very empty, approaching a state of maximum entropy. This is often called the Heat Death of the Universe.

Alternative Endings? (The Cosmic Plot Twists!)

- Big Rip: If dark energy is a "phantom energy" that grows stronger over time, the expansion could accelerate so violently that it rips apart galaxies, stars, planets, atoms, and eventually spacetime itself. Yikes!

- Big Crunch: If the expansion were to reverse (current data says this is unlikely), the Universe would collapse back into a hot, dense singularity, perhaps leading to a new Big Bang (a "Big Bounce"?).

- Vacuum Instability (False Vacuum Decay): What if our Universe's vacuum isn't the true lowest energy state, but just a metastable "false vacuum"? A quantum fluctuation could theoretically tunnel it to a true vacuum state. This new vacuum would expand at the speed of light, rewriting the laws of physics and obliterating everything. Don't lose sleep, the probability is thought to be incredibly tiny!

Threshold 2: Star Power – The Birth and Blazing Lives of Stars

After the Dark Ages, the Universe lit up thanks to stars! These celestial powerhouses are born from collapsing clouds of gas and dust, and they are the cosmic engines that drive much of what happens next. Stars are where the action is, from forging new elements to eventually providing the energy for life.

Stars aren't just pretty lights; they are dynamic, evolving behemoths. They condense from vast, cold molecular clouds (mostly hydrogen and helium, with a sprinkle of heavier "dust"). Gravity pulls these regions together, and as they contract, they heat up.

Most stars don't form alone; they're born in bustling stellar nurseries, in groups ranging from dozens to hundreds of thousands. The most massive stars in these clusters blaze with such intense light they ionize the surrounding hydrogen gas, creating spectacular glowing H II regions. This energetic feedback can eventually blow away the remaining cloud material, halting further star birth in that immediate area.

The vast majority of a star's life is spent on the main sequence, a stable phase where it's primarily fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. But, just like us, stars have different lifespans and life stories depending on their birth mass.

Stellar Classification: The Cosmic Who's Who 譜

Astronomers are like cosmic zoologists, classifying stars based on their spectra (the rainbow of light they emit). This tells us about their temperature, luminosity, and composition. The most common system is the Morgan–Keenan (MK) system: O, B, A, F, G, K, M (Oh Be A Fine Guy/Gal, Kiss Me!). O stars are the hottest, bluest, and most massive, while M stars are the coolest, reddest, and least massive.

The Hertzsprung–Russell (HR) diagram is a crucial tool that plots stars' luminosity against their temperature (or spectral type). Most stars fall along a diagonal band called the main sequence.

(Image: An HR diagram showing the main sequence, giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs.)

(Image: An HR diagram showing the main sequence, giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs.)

| Class | Temperature (K) | Color | Luminosity () | Mass () | Radius () | Abundance (%) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Blue | 0.00003 | Zeta Puppis | ||||

| B | Blue-white | 0.12 | Rigel | ||||

| A | White | 0.61 | Sirius | ||||

| F | Yellow-white | 3 | Procyon | ||||

| G | Yellow | 7.6 | Sun | ||||

| K | Orange | 12 | Epsilon Eridani | ||||

| M | Red | 76 | Proxima Centauri |

Variable Stars: The Drama Queens of the Cosmos Some stars aren't content with a steady glow; their luminosity changes over time!

- Pulsating Variables: These stars literally throb, expanding and contracting like a cosmic heart, causing their brightness to vary (e.g., Cepheid variables, crucial for measuring cosmic distances!).

- Eruptive Variables: These stars have sudden outbursts, like flares or mass ejections (think of our Sun's solar flares, but sometimes much bigger!).

- Cataclysmic Variables: These usually involve binary star systems where one star dumps matter onto a compact companion (like a white dwarf or neutron star), leading to dramatic events like novae (sudden brightening) or even Type Ia supernovae.

Stellar Formation & Evolution: A Star's Life Story

(Image: Diagram showing the life cycles of stars, including low-mass stars like red dwarfs and more massive stars.)

(Image: Diagram showing the life cycles of stars, including low-mass stars like red dwarfs and more massive stars.)

Molecular Cloud Collapse & Protostar Formation: From Dust Bunnies to Baby Stars It all starts in a cold, dense molecular cloud. Something (like a nearby supernova shockwave or a galactic collision) gives a region a gravitational nudge, and if it's dense enough (satisfying the Jeans instability criteria), it starts to collapse under its own gravity.

As bits of the cloud collapse, they form dense clumps called Bok globules. These continue to shrink, and the gravitational potential energy gets converted into heat. Eventually, the core gets hot and dense enough to become a protostar – a baby star not yet shining by nuclear fusion, but glowing from the heat of contraction. Protostars are often shrouded in a disk of gas and dust (a protoplanetary disk – more on that in Threshold 4!) and can shoot out powerful jets of gas called Herbig–Haro objects.

Main Sequence: The Long, Stable Adulthood

When the core of a protostar becomes hot enough and dense enough (millions of Kelvin!), nuclear fusion ignites! Hydrogen atoms start fusing into helium, releasing enormous amounts of energy. This outward radiation pressure balances the inward pull of gravity, and the star enters a long, stable phase called the main sequence. Stars spend about 90% of their lives here. How long they stay depends on their mass:

- Massive stars (O, B types) are like cosmic gas-guzzlers. They burn through their hydrogen fuel incredibly fast and have short main-sequence lives (a few million to tens of millions of years).

- Low-mass stars (K, M types, like red dwarfs) are super frugal. They sip their hydrogen fuel slowly and can live for hundreds of billions, even trillions of years – longer than the current age of the Universe! Our Sun (a G-type star) has a main-sequence lifespan of about 10 billion years (it's about halfway through).

The mass–luminosity relation tells us that more massive stars are much more luminous: where is around 3.5 to 4. So, a star twice as massive as the Sun can be over 10 times more luminous! Stars also have stellar winds, a continuous outflow of particles. For most stars, it's a gentle breeze, but for very massive stars, it can be a gale, shedding significant amounts of mass over their lifetimes.

Post-Main Sequence: The Golden Years & Explosive Endings

What happens when a star runs out of hydrogen fuel in its core? It leaves the main sequence and things get interesting!

Low-Mass Stars (like our Sun, and smaller Red Dwarfs):

- Red Dwarfs (M-type stars, ): These little guys are fully convective, meaning helium doesn't just build up in the core. They burn their hydrogen very slowly and uniformly. When they finally run out (in trillions of years), they are predicted to simply contract into a helium white dwarf and slowly cool down. No dramatic red giant phase for them!

- Sun-like Stars ( to about ):

- Red Giant Phase: When core hydrogen is gone, hydrogen fusion starts in a shell around the now inert helium core. This causes the outer layers of the star to expand enormously (engulfing inner planets!) and cool down, turning it into a red giant. Our Sun will do this in about 5 billion years.

- Helium Flash & Horizontal Branch: As the helium core contracts and heats up (due to the hydrogen shell burning), if the star is less than about , the helium core becomes electron-degenerate (a weird quantum state where pressure doesn't depend on temperature). When it finally gets hot enough for helium to fuse into carbon (via the triple-alpha process), ignition is explosive – a helium flash! The star then shrinks a bit, gets hotter, and settles onto the horizontal branch of the HR diagram, stably fusing helium in its core.

- Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) & Planetary Nebula: After core helium is exhausted, helium starts fusing in a shell around a carbon-oxygen core, and hydrogen may still burn in an outer shell. The star swells up again, becoming even larger and more luminous – this is the AGB phase. These stars experience thermal pulses, becoming unstable and shedding their outer layers into space. This ejected material, illuminated by the hot central core, forms a beautiful, glowing structure called a planetary nebula (a misnomer, nothing to do with planets!).

- White Dwarf: The leftover core, a super-dense ball of carbon and oxygen (mostly), is a white dwarf. It's about the size of Earth but can have up to 1.4 times the Sun's mass (the Chandrasekhar limit). It no longer produces heat through fusion and slowly cools down over billions of years, eventually becoming a cold, dark black dwarf (though the Universe isn't old enough for any black dwarfs to exist yet).

Massive Stars (typically ): Live Fast, Die Young, Go Out with a Bang! These cosmic titans have a much more dramatic and shorter life:

- Supergiant Phases: They also leave the main sequence when core hydrogen is depleted. They become red supergiants (like Betelgeuse) or sometimes blue supergiants, depending on their mass and evolutionary stage. Helium fusion in their core ignites smoothly (no flash for these heavyweights).

- Onion-Layer Fusion: Unlike smaller stars that stop at carbon/oxygen, massive stars are hot and dense enough in their cores to fuse progressively heavier elements: carbon burns to neon and magnesium, neon to oxygen and magnesium, oxygen to silicon and sulfur, and finally silicon to iron. This happens in a series of nested shells, like an onion.

- Iron Core & Core Collapse: Iron is the ultimate cosmic ash for fusion. Fusing iron (or elements heavier than iron) consumes energy instead of releasing it. So, once a massive star builds up an iron core (about ), fusion in the core stops. Gravity takes over catastrophically! The iron core collapses in a fraction of a second from Earth-sized to just a few kilometers across!

- Type II Supernova! The core collapse triggers a shockwave that rebounds outwards, blasting the star's outer layers into space in a titanic explosion called a Type II supernova. For a few weeks, a supernova can outshine its entire host galaxy! This explosion scatters all those heavy elements forged inside the star (and creates even more via the r-process – see Threshold 3!) into the interstellar medium, enriching it for future generations of stars and planets.

- The Remnant:

- Neutron Star: If the collapsing core is between about and (the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit), the collapse is halted by neutron degeneracy pressure (another quantum effect). The result is an incredibly dense neutron star – a city-sized ball of neutrons with the mass of a star! Some rapidly rotating, magnetized neutron stars are observed as pulsars (emitting beams of radiation) or X-ray bursters (if accreting matter in a binary).

- Black Hole: If the core is more massive than about , not even neutron degeneracy pressure can stop the collapse. Gravity wins completely, and the core collapses indefinitely to form a black hole – an object with gravity so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape once it crosses the event horizon.

Wolf–Rayet stars are a special class of very massive, evolved stars () that have lost their outer hydrogen envelope, exposing their hot, helium-rich (or even carbon/oxygen-rich) cores. They have powerful stellar winds and are often supernova progenitors.

Stellar Structure: What's Inside a Star? Stars aren't uniform balls of gas. They have distinct internal layers, primarily determined by how energy is transported outwards:

- Core: The powerhouse! This is the central region where nuclear fusion happens, generating all the star's energy. It's incredibly hot and dense.

- Radiative Zone: Surrounding the core (in Sun-like and more massive stars), energy is transported outwards by photons. Photons generated in the core bounce their way through this dense plasma, a slow "random walk" that can take hundreds of thousands of years to reach the next layer!

- Convective Zone: In the outer layers of Sun-like stars (or throughout lower-mass red dwarfs, and in the cores of very massive stars), energy is transported by convection. Hot plasma physically rises, releases its heat, cools, and then sinks back down to get reheated – like water boiling in a pot.

The specific arrangement of these zones depends on the star's mass.

Threshold 3: Cosmic Kitchens – How Stars Cooked Up the Elements

The Big Bang gave us hydrogen and helium (and a tiny bit of lithium). But look around! We've got carbon, oxygen, iron, gold... all the elements that make up planets, and us! Where did they come from? The answer: stars are cosmic alchemy labs! Through stellar nucleosynthesis, stars fuse lighter elements into heavier ones in their fiery cores and in explosive supernova events.

Stellar Nucleosynthesis: Forging the Building Blocks

Hydrogen Burning: The Main Gig

This is the star's primary fuel source on the main sequence.

- Proton-Proton (PP) Chain: Dominates in cooler, less massive stars like our Sun. It's a series of steps where four hydrogen nuclei (protons) are ultimately converted into one helium-4 nucleus, releasing energy, positrons, and neutrinos.

(Image: Schematic of the Proton-Proton chain reaction, the primary energy source of the Sun.)

(Image: Schematic of the Proton-Proton chain reaction, the primary energy source of the Sun.) - CNO Cycle (Carbon-Nitrogen-Oxygen): Dominates in hotter, more massive stars (roughly ). Carbon, Nitrogen, and Oxygen act as catalysts in a cycle that also fuses four protons into a helium-4 nucleus. It's much more temperature-sensitive than the PP chain.

(Image: The CNO cycle, another hydrogen fusion process prevalent in massive stars.)

(Image: The CNO cycle, another hydrogen fusion process prevalent in massive stars.)

Helium Burning: The Next Course

When core hydrogen is exhausted, and the core heats up to around K, helium fusion kicks in.

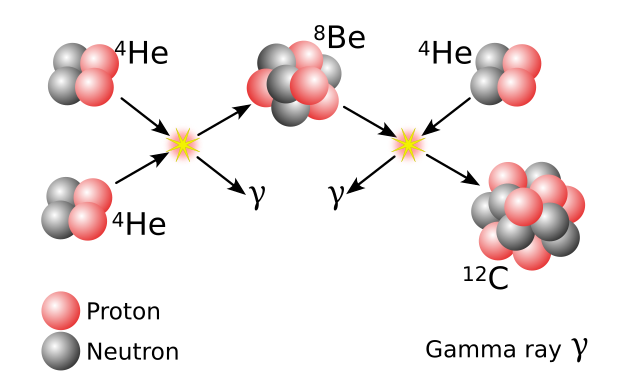

- Triple-Alpha Process: Three helium-4 nuclei (, or alpha particles) combine to form a carbon-12 nucleus (). This is a crucial step, as carbon is the backbone of life! It actually happens in two steps: (Beryllium-8 is unstable), then .

(Image: The triple-alpha process, responsible for carbon production in stars.)

(Image: The triple-alpha process, responsible for carbon production in stars.) - Alpha Process (Alpha Ladder): Once carbon is formed, further captures of alpha particles can produce heavier elements with even numbers of protons, like Oxygen ( from ), Neon ( from ), Magnesium (), Silicon (), etc.

(Image: Alpha process reactions creating heavier elements.)

(Image: Alpha process reactions creating heavier elements.)

Fusion of Heavier Elements: The Massive Star Specialties Only in the cores of massive stars (generally ) do temperatures and pressures get high enough to fuse elements beyond carbon and oxygen. This happens in successive stages as the core contracts and heats up after each fuel is exhausted:

- Carbon Burning ( K): Occurs in the cores of massive stars (at least ). It requires high densities (). (Other products like , also occur.)

- Neon Burning ( K): occurs in evolved massive stars (at least ) that combines neon into other elements. It requires high densities ().

- Oxygen Burning ( K): Occurs in the cores of massive stars that have used up the lighter elements in their cores. It requires high densities ().

- Silicon Burning ( K): This is a complex network of reactions involving photodisintegration and alpha captures, gradually building up elements towards iron. It doesn't burn silicon directly in one step, but rearranges lighter nuclei into heavier ones, ultimately producing elements around iron (like Nickel-56, which then decays to Cobalt-56 and then to stable Iron-56).

Fusion reactions stop producing net energy at iron () because its nucleus is one of the most tightly bound. To fuse iron into heavier elements requires energy input, rather than releasing it. So, when an iron core builds up in a massive star, the party's over for fusion energy production! This leads to core collapse and a supernova.

Neutron Capture Processes: Making the Really Heavy Stuff! How do we get elements heavier than iron, like gold, silver, lead, and uranium? Fusion won't do it. The answer is neutron capture:

- s-process (slow neutron capture): This happens in the late stages of relatively low-to-intermediate mass stars (like AGB stars). Neutrons are captured one by one. If the new nucleus is unstable, it has time to undergo beta decay (a neutron turns into a proton, increasing the atomic number by one) before another neutron comes along. It's a slow, step-by-step build-up, creating many isotopes along the valley of beta stability up to bismuth.

- r-process (rapid neutron capture): This requires an environment with an incredibly high density of neutrons, like the explosive conditions of a core-collapse supernova or the merger of two neutron stars. Nuclei are bombarded with so many neutrons so quickly that they don't have time to beta decay until after the neutron flood is over. This allows them to jump over instability gaps and create very heavy, neutron-rich isotopes, including elements like gold, platinum, and uranium.

So, next time you see a gold ring, remember: that gold was likely forged in the cataclysmic collision of neutron stars or a massive stellar explosion! You're wearing star-stuff, big time!

Threshold 4: Worlds in the Making – Planets, the Cradles of Possibility

With stars blazing and elements cooking, the stage is set for the next level of complexity: planets! These are the celestial bodies that, under the right conditions, can become the nurseries for life. Our own Solar System is a fantastic case study.

The Birth of Our Solar System: From Nebula to Neighborhood

Our Solar System didn't just pop into existence. It formed about 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a giant fragment of a cold, dense molecular cloud (often called the presolar nebula or solar nebula). What kicked off this collapse? Probably a nearby event, like a shockwave from a supernova or disturbances from a passing star, compressing parts of the cloud. Our Sun likely wasn't born alone; it probably formed within a stellar cluster of thousands of stars. Over time, this cluster dispersed, and our Sun went its own way.

- Spinning Up and Flattening Out: As the chosen fragment of the nebula collapsed, it began to spin faster due to the conservation of angular momentum (like an ice skater pulling in their arms). This spinning motion, combined with gravity and gas pressure, caused the cloud to flatten into a rotating disk of gas and dust called a protoplanetary disk, with a hot, dense protostar (the baby Sun) forming at its center. This disk was huge, maybe 200 Astronomical Units (AU) across (1 AU is the Earth-Sun distance).

- Ignition! After about 100,000 years of contraction, the core of the protostar became so hot and dense (millions of degrees!) that hydrogen fusion ignited. Our Sun lit up, entering its main sequence phase, and a star was born!

Planet Formation: From Dust Bunnies to Worlds

The planets we know and love (and the asteroids, comets, etc.) all formed from the leftover material in that protoplanetary disk around the young Sun. It's a process called accretion:

- Dust to Pebbles: Tiny dust grains in the disk started sticking together through electrostatic forces and other microphysical processes, forming larger clumps, then pebble-sized objects.

- Pebbles to Planetesimals: These pebbles continued to collide and merge, growing into kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals. Gravity starts to play a more significant role here.

- Planetesimals to Protoplanets: Planetesimals gravitationally attracted each other, leading to more collisions and mergers. The bigger ones grew faster, sweeping up smaller ones, eventually forming protoplanets – objects roughly Moon-to-Mars sized.

- Protoplanets to Planets: The final stage involved giant impacts between these protoplanets over tens to hundreds of millions of years, sculpting them into the planets we see today.

The Frost Line: A Cosmic Dividing Line The temperature in the protoplanetary disk wasn't uniform. It was hotter near the young Sun and cooler further out. A crucial dividing line was the frost line (or snow line), located somewhere between the current orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

- Inner Solar System (Inside the Frost Line): It was too warm for volatile compounds like water, methane, and ammonia to condense into ice. So, planets here formed mainly from rocky silicates and metals (which were much rarer in the nebula, only ~0.6% of its mass). This is why Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars are rocky terrestrial planets.

- Outer Solar System (Beyond the Frost Line): It was cold enough for those volatile ices to form. Since ice was much more abundant than rock and metal, the protoplanets here could grow much larger, much faster.

The Giant Planets: Kings of the Outer Realm Jupiter and Saturn, the gas giants, grew so massive (by accreting icy planetesimals and then large amounts of gas) that their gravity allowed them to capture enormous atmospheres of hydrogen and helium – the most abundant elements in the nebula. Uranus and Neptune, the ice giants, formed a bit later and further out, when much of the gas had been blown away by the Sun's stronger early stellar wind. They captured less hydrogen and helium but are rich in ices like water, ammonia, and methane. The immense gravity of Jupiter, in particular, likely prevented a planet from forming in the region between Mars and Jupiter, instead stirring up the planetesimals there and leading to the formation of the asteroid belt.

Clearing the Disk: After a few million to perhaps ten million years, the young Sun's powerful solar wind and radiation pressure swept away most of the remaining gas and dust from the protoplanetary disk, ending the primary phase of planet growth.

Subsequent Evolution: A Dynamic Youth The early Solar System was a chaotic place!

- Planetary Migration: The giant planets likely didn't form in their current orbits. Interactions with the remaining gas disk and with each other probably caused them to migrate significantly. Some models (like the "Nice model") suggest dramatic shifts in their positions.

- Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB): Around 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago, the inner Solar System experienced a period of intense asteroid and comet impacts. This might have been triggered by the migration of the giant planets, which would have gravitationally scattered vast numbers of smaller bodies. The Moon's heavily cratered surface is a testament to this era.

- Formation of the Moon (Giant Impact Hypothesis): Our Moon is thought to have formed from a colossal collision between the early Earth and a Mars-sized protoplanet nicknamed Theia. The debris from this impact was ejected into orbit around Earth and eventually coalesced to form the Moon. This explains the Moon's composition and relative lack of a large iron core.

The Cosmic Hierarchy: Our Place in the Grand Scheme ️

Our Earth isn't just floating in an undefined void. It's part of a vast, nested structure of cosmic systems. Let's zoom out!

(Image: Earth's location in the Universe, showing nested structures.)

(Image: Earth's location in the Universe, showing nested structures.)

| Level | Approximate Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Earth | km | Our home! The third rock from the Sun, teeming with life (so far, the only one we know for sure!). |

| Solar System | AU (to Neptune) | Our Sun and its family: planets, moons, asteroids, comets. The heliosphere extends much further. |

| Local Interstellar Cloud | light-years (ly) | The small cloud of interstellar gas our Solar System is currently passing through. |

| Local Bubble | ly | A relatively empty, hot cavity in the interstellar medium, likely carved out by ancient supernovae. Our Local Interstellar Cloud is within this bubble. |

| Gould Belt | ly | A partial ring of young, massive stars and star-forming regions, tilted with respect to the Milky Way's disk. Our Sun is near its edge. |

| Orion Arm (Orion-Cygnus Arm) | ly long, ly wide | A minor spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy where our Solar System resides. |

| Milky Way Galaxy | ly diameter | Our home galaxy! A vast barred spiral galaxy containing 100-400 billion stars. We're about 27,000 ly from its supermassive black hole center (Sagittarius A*). |

| Milky Way Subgroup | Mly | The Milky Way and its retinue of smaller satellite galaxies (like the Magellanic Clouds). |

| Local Group | Mly | A group of over 80 galaxies, dominated by the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), which are on a collision course! Also includes the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) and many dwarfs. |

| Local Sheet (Council of Giants) | Mly | A flattened arrangement of nearby galaxies, including the Local Group, that lies within the Virgo Supercluster. |

| Virgo Supercluster | Mly | A massive supercluster containing thousands of galaxies, including the Local Group (which is on its outskirts). Dominated by the Virgo Cluster near its center. |

| Laniakea Supercluster | Mly | Our "home" supercluster! An even vaster structure defined by galactic motions, with galaxies flowing towards a central region called the Great Attractor. Includes Virgo. |

| Local Hole (or KBC Void) | Bly | Our galaxy might be in a relatively large, underdense region of space, a cosmic void, compared to the average density of the Universe. |

| Observable Universe | Billion light-years diameter | The spherical region of the Universe comprising all matter that can be observed from Earth at present, because light from these objects has had time to reach us since the Big Bang. |

| Universe | Potentially infinite | The entirety of space, time, matter, and energy. The observable Universe is just the part we can see; the actual Universe could be vastly larger, perhaps even infinite. |

(Image: A logarithmic map showing the scale of the observable Universe with Earth at the center.)

(Image: A logarithmic map showing the scale of the observable Universe with Earth at the center.)

Threshold 5: Life – The Emergence of Life on Earth

With planets formed, some, like our Earth, found themselves in the "Goldilocks zone" – not too hot, not too cold, just right for liquid water, a key ingredient for life as we know it. This threshold marks one of the most profound transformations: the leap from non-living chemistry to self-replicating, evolving life. This happened relatively early in Earth's history, around 3.5 to 4 billion years ago.

The story of life is written in the rocks and the genes of every living thing, a tale spanning eons, mass extinctions, and incredible bursts of creativity. Here's a whirlwind tour through Earth's geological and biological timeline, with a focus on tectonic activity that shaped our world:

Precambrian Supereon: The Long Dawn (Roughly 4.6 bya – 541 mya)

This supereon covers almost 90% of Earth's history! It's when the very first life appeared and slowly set the stage for more complex forms.

| Eon | Subdivision | Time Range (approx.) | Key Life & Tectonic Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hadean | – | ~4.6 – 4.0 bya | "Hellish Earth"! Formation of Earth, Giant Impact forming the Moon, Late Heavy Bombardment. Molten surface, intense volcanism. Early, vigorous mantle convection; perhaps proto-tectonic processes creating short-lived crustal fragments. |

| Archean | Eoarchean | ~4.0 – 3.6 bya | Oceans form. Earliest chemical evidence of life (around 3.8 bya), first stromatolites (fossilized microbial mats, ~3.5 bya) in a reducing (low-oxygen) atmosphere. Formation of small microcontinents (cratons) and greenstone belts. |

| Paleoarchean | ~3.6 – 3.2 bya | Proliferation of simple, anaerobic (non-oxygen-using) microbial life (prokaryotes). Continued craton formation; possible assembly of the first supercontinent, Vaalbara. | |

| Mesoarchean | ~3.2 – 2.8 bya | Microbial ecosystems expand. More stable cratons develop. | |

| Neoarchean | ~2.8 – 2.5 bya | Increasing geological stability. Oxygenic photosynthesis likely begins with cyanobacteria, starting to slowly add oxygen to the atmosphere. Formation of supercontinent Kenorland. |

Proterozoic Eon: The Oxygen Revolution & First Eukaryotes (2.5 bya – 541 mya)

A time of dramatic environmental change and crucial evolutionary steps. The Great Oxidation Event (GOE): Around 2.45 bya, oxygen produced by cyanobacteria started to build up significantly in the atmosphere. This was initially toxic to much existing anaerobic life but paved the way for more complex, oxygen-breathing organisms. Massive Banded Iron Formations were deposited as dissolved iron in the oceans reacted with this new oxygen.

| Era | Period | Time Range (approx.) | Key Life & Tectonic Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleoproterozoic | Siderian | ~2.5 – 2.3 bya | Great Oxidation Event in full swing. Supercontinent Columbia (Nuna) begins to assemble. |

| Rhyacian | ~2.3 – 2.05 bya | First major glaciations (Huronian). First eukaryotes evolve (cells with a nucleus), possibly through endosymbiosis (an archaeon engulfing an alphaproteobacterium, which became mitochondria). | |

| Orosirian | ~2.05 – 1.8 bya | Oxygen levels rise. Major asteroid impacts (e.g., Vredefort). Columbia continues assembly. | |

| Statherian | ~1.8 – 1.6 bya | Complex single-celled life diversifies. Columbia is largely assembled. | |

| Mesoproterozoic | Calymmian | ~1.6 – 1.4 bya | Development of stable continental platforms. Supercontinent Rodinia begins to assemble. Sexual reproduction likely evolves in eukaryotes, speeding up evolution. |

| Ectasian | ~1.4 – 1.2 bya | Earliest evidence of multicellular algae (e.g., red algae). Rodinia continues to form. | |

| Stenian | ~1.2 – 1.0 bya | Rodinia is fully assembled. Early forms of multicellularity might be more common. | |

| Neoproterozoic | Tonian | ~1.0 – 0.72 bya | Breakup of Rodinia begins. Early evidence of animal-like multicellular organisms (sponges?). |

| Cryogenian | ~0.72 – 0.635 bya | Extreme global glaciations: "Snowball Earth" episodes (Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations). Life survives in refugia. Potential trigger for the evolution of more complex animals. | |

| Ediacaran | ~0.635 – 0.541 bya | After Snowball Earth, emergence of the Ediacaran biota – large, enigmatic, soft-bodied multicellular organisms. First clear evidence of animal life. Supercontinent Pannotia forms and then begins to break apart. |

Phanerozoic Eon: Visible Life! (541 mya – Present)

The eon of "visible life," characterized by abundant fossils and the diversification of complex animals and plants.

| Era | Period | Time Range (approx.) | Key Life & Tectonic Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleozoic (Ancient Life) | Cambrian | ~541 – 485 mya | Cambrian Explosion: Rapid diversification of most major animal phyla with hard shells and skeletons. Gondwana is a major supercontinent. |

| Ordovician | ~485 – 444 mya | Diverse marine invertebrates (trilobites, brachiopods, corals). First primitive jawless fish. Ends with a major extinction event (Ordovician-Silurian extinction). Gondwana drifts south. | |

| Silurian | ~444 – 419 mya | First terrestrial life: simple plants (like mosses), fungi, and arthropods (millipedes, scorpions) colonize land. First jawed fish evolve. Continents (Laurentia, Baltica, Avalonia) collide to form Euramerica. | |

| Devonian | ~419 – 359 mya | "Age of Fishes" – great diversification of fish, including sharks and bony fish. First amphibians (tetrapods) venture onto land. First seed plants (ferns, early trees) form forests. Late Devonian extinction affects marine life. | |

| Carboniferous | ~359 – 299 mya | Vast swamp forests (source of modern coal deposits). Amphibians thrive. First reptiles evolve. Insects grow to giant sizes due to high oxygen levels. Supercontinent Pangaea begins to assemble. | |

| Permian | ~299 – 252 mya | Reptiles diversify (ancestors of mammals and dinosaurs appear). Pangaea fully assembled. Ends with the Permian-Triassic Extinction ("The Great Dying"), the largest mass extinction in Earth's history (wiped out ~96% of marine species and ~70% of terrestrial vertebrate species). | |

| Mesozoic (Middle Life - "Age of Reptiles") | Triassic | ~252 – 201 mya | Life recovers from the P-T extinction. First dinosaurs and first true mammals evolve. Pangaea begins to rift apart. |

| Jurassic | ~201 – 145 mya | Dinosaurs dominate the land. Giant sauropods, carnivorous theropods. First birds (like Archaeopteryx) evolve from feathered dinosaurs. Pangaea continues to break up into Laurasia and Gondwana; Atlantic Ocean begins to form. | |

| Cretaceous | ~145 – 66 mya | Dinosaurs continue to dominate. Flowering plants (angiosperms) appear and diversify. Ends with the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) Extinction event (likely caused by an asteroid impact, wiping out non-avian dinosaurs). Modern continents take shape. |

Cenozoic Era: "Age of Mammals" (66 mya – Present)

| Period | Epoch | Time Range (approx.) | Key Life & Tectonic Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleogene | Paleocene | ~66 – 56 mya | Mammals, birds, and flowering plants rapidly diversify to fill ecological niches left vacant by dinosaurs. India begins its collision with Asia, starting the Himalayan uplift. |

| Eocene | ~56 – 33.9 mya | Warm global climate. Early primates, whales, and other modern mammal groups appear. Grasslands expand. | |

| Oligocene | ~33.9 – 23 mya | Cooling trend. Antarctica becomes glaciated. Spread of grasslands continues. | |

| Neogene | Miocene | ~23 – 5.3 mya | Further cooling and drying. Apes diversify in Africa. Kelp forests appear. Uplift of major mountain ranges like the Andes and Rockies continues. |

| Pliocene | ~5.3 – 2.6 mya | Global cooling intensifies, leading to the onset of Quaternary ice ages. Hominins (early human ancestors like Australopithecus) evolve in Africa. Isthmus of Panama forms, linking North and South America. | |

| Quaternary | Pleistocene | ~2.6 mya – 11,700 ya | "Ice Age." Repeated glacial cycles (glacials and interglacials). Evolution and dispersal of the genus Homo, including Homo erectus, Neanderthals, and anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). Megafauna (mammoths, sabertooths). |

| Holocene | ~11,700 ya – Present | Current interglacial period. Retreat of glaciers. Rise of human civilization, agriculture, development of complex societies. | |

| Anthropocene | (Proposed) Current | (Unofficial epoch) Characterized by significant human impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems. |

And here's a glimpse of how our continents have danced around over the past billion years!

*(Video: Animation showing tectonic plate movement over the last billion years.)*Thresholds 6, 7 & 8: The Human Saga – Intelligence, Farming, & Warp Speed Modernity

Within the grand tapestry of life, one lineage – hominins – embarked on a path leading to extraordinary cognitive abilities. The emergence of human intelligence (Threshold 6) wasn't just about bigger brains; it was about complex language, abstract thought, symbolic culture, and the ability to learn collectively and pass knowledge across generations. This set the stage for even more rapid transformations.

The invention of agriculture around 10,000-12,000 years ago (Threshold 7) was a game-changer. It allowed humans to settle in one place, produce food surpluses, and support larger populations. This led to villages, then cities, specialized labor, social hierarchies, and eventually, complex civilizations with writing, laws, and monumental architecture.

Finally, Threshold 8 marks the acceleration to modernity, particularly supercharged by the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolutions. This period saw an explosion in scientific understanding, technological innovation, global interconnectedness, and population growth, fundamentally reshaping human societies and our planet at an unprecedented rate.

Here’s a broad-strokes timeline of these human-centric thresholds:

| Age/Period | Approximate Time Range | Key Characteristics & Events – The Human Story Unfolds! |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Paleolithic | ~3.3/2.5 million – ~300,000 ya | Tool Time Begins! Early hominins like Australopithecus (possibly first tool users, Lomekwian tools ~3.3 mya) and later Homo habilis (Oldowan tools ~2.5 mya) start making simple stone tools. Homo erectus appears, masters fire, and ventures out of Africa. |

| Middle Paleolithic | ~300,000 – ~50,000 ya | Smarter Tools, Bigger Brains! More sophisticated tool-making (e.g., Mousterian by Neanderthals). Homo neanderthalensis thrives in Europe/Asia. Early Homo sapiens appear in Africa. Evidence of burial, perhaps early symbolic behavior. |

| Upper Paleolithic | ~50,000 – ~12,000 ya | The Creative Explosion! Anatomically modern Homo sapiens spread across the globe. Development of complex language, sophisticated blade tools, bone tools, projectile weapons. Flourishing of cave art, figurines, personal adornment. Last Ice Age peaks. |

| Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) | ~12,000 – ~10,000 ya (varies) | Adapting to a New World! Transition period as the Ice Age ends. Hunter-gatherer-fisher societies adapt to changing environments. Development of smaller, more refined stone tools (microliths). Bows and arrows. Canoes. |

| Neolithic (New Stone Age) | ~10,000 – ~4,500 BCE (varies) | The Agricultural Revolution! Domestication of plants and animals begins independently in various regions (Fertile Crescent, China, Mesoamerica, etc.). Shift from nomadic hunting/gathering to settled farming villages. Pottery. Polished stone tools. Megalithic structures. |

| Chalcolithic (Copper Age) | ~4500 – ~3300 BCE (varies) | Metal Gets Interesting! First use of copper for tools and ornaments, alongside stone. Early experiments with metallurgy. Increasing social complexity, larger settlements. |

| Bronze Age | ~3300 – ~1200 BCE (varies) | Civilizations Rise! Widespread use of bronze (copper + tin alloy) for weapons, tools, art. Emergence of the first true cities, states, writing systems (Mesopotamia, Egypt, Indus Valley, China). Chariots. Long-distance trade. |

| Iron Age | ~1200 BCE – Classical Era (varies) | Iron Sharpens Iron! Iron smelting technology spreads, leading to stronger, cheaper tools and weapons. Empires rise and fall (Assyrians, Persians). Alphabetic writing develops. Coinage. |

| Classical Antiquity | ~8th century BCE – ~5th century CE | Golden Ages of Thought! Flourishing of Greek and Roman civilizations. Major developments in philosophy (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle), democracy, mathematics, science, literature, art, architecture, law. Rise of major religions. |

| Late Antiquity | ~3rd – ~7th century CE | Transition Time! Decline of the Western Roman Empire. Rise of Byzantine Empire. Spread of Christianity and later Islam. Migrations and formation of new kingdoms in Europe. |

| Middle Ages (Medieval Period) | ~5th – ~15th century CE | Feudalism & Faith! In Europe: Feudal system, manorialism, rise of powerful Church, Crusades, Gothic architecture. Islamic Golden Age: Major advances in science, math, medicine, philosophy. Dynasties in China, India, Americas. |

| Renaissance | ~14th – ~17th century CE | Rebirth of Ideas! "Rebirth" of classical art, literature, and philosophy in Europe. Humanism. Scientific inquiry begins to challenge old views (Copernicus, Galileo). Printing press revolutionizes information spread. |

| Age of Discovery (Exploration) | ~15th – ~18th century CE | New Worlds, Global Connections! European maritime exploration leads to global mapping, circumnavigation, establishment of colonial empires, and the Columbian Exchange (widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, people, tech, diseases, ideas). |

| Scientific Revolution & Enlightenment | ~16th – ~18th century CE | Reason Reigns! Development of the scientific method (Bacon, Descartes). Breakthroughs by Newton, Kepler. Emphasis on reason, individualism, human rights, skepticism of tradition. Influences revolutions (American, French). |

| Industrial Revolution(s) | ~1760 – ~1914 CE (First & Second) | Machines Change Everything! Transformation from agrarian to industrial societies. Steam power, factories, urbanization (First IR). Later, electricity, steel, chemicals, internal combustion engine, mass production (Second IR). Profound social and economic changes. |

| "Modern" Era (Imperial/World Wars/Cold War) | ~19th – late 20th century CE | Rise of nation-states, ideologies (capitalism, communism, fascism), global empires (e.g., British "Imperial Century"), World Wars, nuclear age, Cold War, decolonization. The "American Century" emerges post-WWII. |

| Digital Age / Information Age | Late 20th century – Present | The Connected World! Development of computers, internet, mobile tech, AI. Globalization accelerates. Instant communication, vast information access. Unprecedented technological and social change. |

| Contemporary Age (Anthropocene?) | Ongoing | Characterized by rapid innovation, global challenges (climate change, pandemics, resource scarcity), and the profound impact of human activity on the planet (leading to the proposed "Anthropocene" epoch). |

Key Takeaways From Our Cosmic Chronicle!

What a whirlwind tour through 13.8 billion years! From the faintest flicker of the Big Bang to the complex tapestry of human civilization, the Universe has been on an incredible journey of increasing complexity. Let's recap the highlights of our eight thresholds:

- Threshold 1: The Big Bang & Creation: The Universe bursts into existence from an incredibly hot, dense state, undergoing rapid inflation, forming the first particles, and setting the stage with light elements and the Cosmic Microwave Background.

- Threshold 2: Stars Light Up: Gravity pulls matter together to form the first stars, igniting nuclear fusion and bathing the young Universe in light, ending the Cosmic Dark Ages. Stars become the Universe's engines.

- Threshold 3: Forging New Elements: Stars act as cosmic furnaces, fusing hydrogen and helium into heavier elements like carbon, oxygen, and iron. Supernovae and neutron star mergers create the heaviest elements, scattering them into space.

- Threshold 4: Planets Form: Around stars, leftover gas and dust accrete to form planets and solar systems, creating diverse worlds, some of which might be suitable for life.

- Threshold 5: Life Emerges: On at least one planet, Earth, complex chemistry under the right conditions gives rise to self-replicating life, leading to billions of years of biological evolution, from simple microbes to complex plants and animals.

- Threshold 6: Human Intelligence Dawns: A specific lineage of primates evolves significantly larger brains and the capacity for symbolic language, collective learning, and complex problem-solving, marking the rise of Homo sapiens.

- Threshold 7: Agriculture & Civilization: Humans learn to domesticate plants and animals, leading to settled societies, food surpluses, population growth, cities, and the first complex civilizations with specialized roles and recorded history.

- Threshold 8: Modernity & Acceleration: The pace of change skyrockets with scientific revolutions, industrialization, and the digital age, leading to our current globally interconnected, technologically advanced, and rapidly evolving world.

Each threshold built upon the last, creating new possibilities and more intricate structures. It's a story of cosmic evolution, stellar alchemy, planetary formation, biological adaptation, and human ingenuity. And the best part? The story is still unfolding! What will the next threshold be?