Fluids Unleashed - The Wild Physics of Liquids & Gases!

Hey flow-fanatics and pressure-puzzlers! Ever stopped to think about the stuff that, well, flows? We're talking about fluids – a super cool category that includes both liquids (like your morning coffee ☕) and gases (like the air you're breathing right now!). They're everywhere, from the gentle lapping of a lake to the powerful gusts of a storm, and even coursing through our own veins!

Understanding the mechanical properties of these flowing wonders is like unlocking a secret language of nature. It helps us design super-efficient airplanes, build sturdy dams, and even understand how tiny dewdrops form. In this post, we're taking a deep dive into the fascinating realm of fluids, exploring the mysteries of pressure, the magic of buoyancy, the delicate dance of surface tension, the sticky situation of viscosity, and the grand principles that make fluids groove. So, let's get ready to go with the flow!

The Pressure Cooker: Understanding Fluid Weight & Force ️

One of the most fundamental properties of a fluid is the pressure it exerts. It’s like the collective push of all those tiny fluid particles!

The Weight of a Liquid Column: Pressure Due to Gravity

Imagine a column of water. The water at the bottom has to support the weight of all the water above it. This is why pressure increases the deeper you go! The pressure () at a certain depth () in a fluid at rest is given by a beautifully simple equation: Where:

- (rho) is the density of the fluid (how much "stuff" is packed into it).

- is the acceleration due to gravity (that trusty on Earth).

- is the depth from the surface.

Let's Derive It! (It's Easier Than You Think!) Consider a tiny, imaginary cylinder of fluid with height and cross-sectional area , located at a depth .

- The volume of this tiny cylinder is .

- Its mass .

- The weight of this tiny cylinder is .

- This weight pushes down on the area at its base, creating a small pressure difference . Pressure is force per unit area, so .

- To find the total pressure at a depth , we add up (integrate) all these tiny pressure contributions from the surface (where pressure due to the liquid is 0, assuming we ignore atmospheric pressure for a moment or set ) down to depth : Assuming and are constant with depth (a good assumption for most liquids):

Voilà! The deeper you go, the more squished you get!

Pascal's Law: The Force Multiplier Magic!

Blaise Pascal, a brilliant mind, figured out something super neat about pressure in confined fluids. Pascal's Law states that if you apply pressure to an enclosed, incompressible fluid, that pressure is transmitted undiminished to every part of the fluid and to the walls of its container. It's like an instant pressure-sharing network!

Applications? Oh, They're BIG!

- Hydraulic Lift: This is where Pascal's Law really shines as a force multiplier. Imagine two connected cylinders, one with a small piston (area ) and one with a large piston (area ). If you apply a small force to the small piston, it creates a pressure . Pascal says this pressure is transmitted equally throughout the fluid, so . The force on the large piston is . Since is much larger than , is much larger than ! This is how hydraulic jacks lift cars with relatively little effort. It's not free energy (you push the small piston a longer distance), but it's a fantastic way to amplify force.

- Hydraulic Brakes: Your car's brakes use the same principle. You push the brake pedal (small force on a small piston), this creates high pressure in the brake fluid, which is then transmitted to larger pistons in the brake calipers, clamping down on the wheels with a much greater force. Safety first, thanks to Pascal!

Gravity's Grip: Effect of Gravity on Fluid Pressure in Tilted Systems

What if your container of water is tilted? Does still hold? Yes, but is always the vertical depth from the point to the free surface of the liquid. If you measure depth along a line that's not vertical, things get a bit more nuanced. If is the angle between the vertical and a line of length connecting the point to the free surface, the vertical depth . If we are considering the pressure relative to the pressure at the free surface: Or, if is the vertical depth component, it remains . The pressure at a point only depends on the vertical height of the fluid column directly above it (and the surface pressure).

Floating & Sinking: The Archimedes Splash! eureka

Why does a huge steel ship float, but a tiny pebble sinks? Enter Archimedes of Syracuse and his famous principle! Archimedes' Principle states that an object wholly or partially immersed in a fluid experiences an upward buoyant force () equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. Where:

- is the density of the fluid.

- is the volume of the fluid that the object pushes out of the way (which is equal to the volume of the submerged part of the object).

So, an object floats if the buoyant force is greater than or equal to its own weight (). It sinks if its weight is greater. It's a density game! A ship floats because its overall average density (steel + all the air inside) is less than the density of water.

The Skin of a Drink: Surface Tension Surprises!

Ever seen a water strider skate effortlessly on a pond? Or noticed how water forms beads on a freshly waxed car? That's surface tension at work! It’s like an invisible, elastic "skin" on the surface of a liquid.

Surface tension (, gamma) arises because the molecules within the liquid are attracted to each other by intermolecular forces (cohesion). Molecules at the surface don't have neighbors above them, so they experience a net inward pull from the molecules below and beside them. This inward pull tries to minimize the surface area of the liquid. Surface tension is defined as the force () per unit length () acting perpendicular to an imaginary line segment on the liquid surface: Its units are typically Newtons per meter (N/m).

Angle of Contact: To Wet or Not to Wet?

When a liquid meets a solid surface, the edge of the liquid forms an angle of contact (). This angle tells us about the balance between:

-

Cohesive forces: Attraction between liquid molecules.

-

Adhesive forces: Attraction between liquid molecules and solid surface molecules.

-

If adhesive forces are stronger (e.g., water on clean glass), the liquid "wets" the surface, and .

-

If cohesive forces are stronger (e.g., mercury on glass, or water on a waxy surface), the liquid tries to "ball up," minimizing contact, and .

Excess Pressure Across a Curved Surface: The Bubble's Secret

Because of surface tension, there's a pressure difference across a curved liquid surface. The pressure inside a curved surface (like a droplet or a bubble) is slightly higher than the pressure outside. For a spherical droplet of radius : For a soap bubble (which has two surfaces, inner and outer), this excess pressure is . This is why it takes effort to blow up a bubble!

Applications: Drops, Bubbles, and Amazing Rises!

- Drops and Bubbles: Surface tension pulls liquid into spherical shapes because a sphere has the smallest surface area for a given volume.

- Capillary Action (Rise/Fall): This is the cool effect where a liquid rises up (or is depressed in) a narrow tube (a capillary). It's due to the interplay of surface tension and adhesive/cohesive forces. If a liquid wets the tube (), the adhesive forces pull the liquid up the sides, and surface tension tries to flatten the curved meniscus, pulling the whole column up until its weight is balanced by the upward surface tension force component. The height () of capillary rise is given by: Where is the radius of the capillary tube. If (liquid doesn't wet the tube, like mercury in glass), is negative, and is negative, meaning the liquid level is depressed.

Gooey or Runny? The Secrets of Viscosity!

Ever tried to race honey against water? Water wins, obviously! That's because honey is much more "gooey" or, in physics terms, has a higher viscosity. Viscosity (, eta) is a measure of a fluid's resistance to flow. It's essentially fluid friction. High viscosity means it resists flow (like molasses); low viscosity means it flows easily (like water or air).

When a fluid flows over a surface, or when layers of fluid flow past each other at different speeds, there's an internal friction. The force needed to maintain this flow is related to the shear stress (), which is the force per unit area acting parallel to the fluid layers. For many fluids (Newtonian fluids), this shear stress is proportional to the rate of shear strain, or velocity gradient (), which is how much the fluid velocity changes with distance perpendicular to the flow: The constant of proportionality is the dynamic viscosity (). Its units are Pascal-seconds (Pa·s) or Poise (1 Pa·s = 10 Poise).

Stokes' Law: Dragging Through the Goo

When a small sphere moves slowly through a viscous fluid, it experiences a drag force. Sir George Stokes figured this one out. Stokes' Law gives the drag force () on a sphere of radius moving at a constant velocity through a fluid of viscosity : This law is super useful but generally applies only for low Reynolds numbers (smooth, laminar flow).

Reynolds Number (Re): The Flow's Personality Test Is the flow smooth and orderly (laminar) or chaotic and swirly (turbulent)? The Reynolds number (Re), a dimensionless quantity, helps us predict this: Where:

- is fluid density.

- is a characteristic fluid velocity.

- is a characteristic linear dimension (e.g., pipe diameter).

- is dynamic viscosity.

Generally:

- : Flow is likely laminar.

- : Flow is likely turbulent.

- In between: It's a transition zone.

Terminal Velocity: The Skydiving Limit

When an object falls through a fluid (like a skydiver through air, or a tiny bead in oil), it initially accelerates due to gravity. But as its speed increases, the drag force (which depends on velocity, e.g., Stokes' Law or at higher speeds) also increases. Eventually, the drag force becomes equal to the gravitational force (minus any buoyant force). At this point, the net force is zero, and the object stops accelerating, falling at a constant speed called terminal velocity ().

For a sphere falling under gravity, considering buoyant force () and Stokes' drag: Net downward force (weight) . Upward buoyant force . Upward drag force . At terminal velocity, : Solving for :

The Flowing Symphony: Bernoulli's Principle & Beyond!

How do airplanes fly? Why does a curveball curve? Daniel Bernoulli gave us a key piece of the puzzle!

Flow Regimes: Smooth Sailing or Wild Rapids?

- Streamline (Laminar) Flow: Fluid particles move in smooth, parallel paths (layers or "laminae"). Think of a slow, steady river.

- Turbulent Flow: Fluid particles move in irregular, chaotic, swirling patterns (eddies). Think of whitewater rapids or smoke billowing.

- Critical Velocity: The velocity at which flow transitions from laminar to turbulent. Depends on Re.

Bernoulli's Principle: The Speed-Pressure Trade-off!

For an ideal fluid (incompressible, non-viscous) in steady, streamline flow, Bernoulli's Principle states that along a streamline, the sum of the pressure, the kinetic energy per unit volume, and the potential energy per unit volume remains constant. Where:

- is the fluid pressure.

- is the fluid density.

- is the fluid velocity.

- is acceleration due to gravity.

- is the height above a reference level.

This beautifully simple equation tells us something profound: where the speed of a fluid is high, its pressure is low, and vice-versa (assuming height changes are negligible or accounted for).

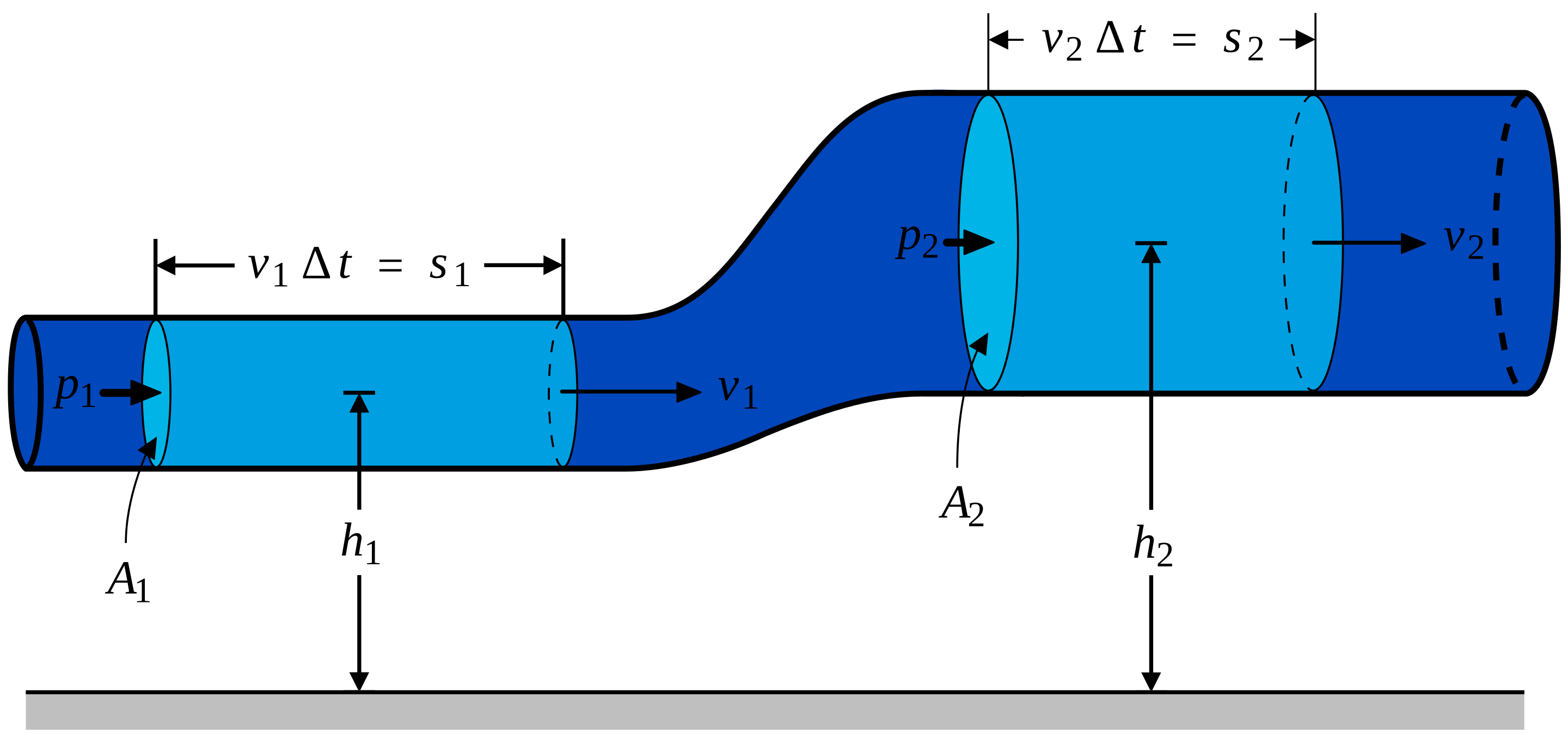

(Image: Fluid flowing through a pipe of varying cross-section and height, illustrating concepts used in Bernoulli's equation derivation.)

(Image: Fluid flowing through a pipe of varying cross-section and height, illustrating concepts used in Bernoulli's equation derivation.)

Let's Derive Bernoulli's Equation (Work-Energy Style!): Consider a small mass of an ideal fluid moving along a streamline from point 1 to point 2.

- Work done by pressure forces: At point 1, force is . If fluid moves a distance , work done on the fluid is . At point 2, force is . If fluid moves , work done by the fluid is . The volume . Net work by pressure: .

- Work done by gravity: Change in potential energy is . Work done by gravity .

- Change in kinetic energy: .

According to the Work-Energy Theorem, the total work done by non-conservative forces (here, pressure) equals the change in mechanical energy (KE + PE): Divide by and rearrange: Multiply by : This confirms that is constant along a streamline.

Applications That Take Flight (and Spray!):

- Airplane Wings (Airfoils): The curved top surface of a wing forces air to travel faster over it than the air traveling under the flatter bottom surface. Faster air on top means lower pressure (Bernoulli!). Slower air below means higher pressure. This pressure difference creates an upward force called lift!

- Venturi Effect: If you narrow a pipe (a Venturi), the fluid speeds up as it passes through the constriction (to maintain constant flow rate – equation of continuity ). Bernoulli says this increased speed means decreased pressure in the narrow section. This is used in carburetors (to draw fuel into the airflow) and perfume atomizers/paint sprayers.

The Master Equations: Navier-Stokes – Fluid Dynamics' Grand Opus!

For real-world fluids (which do have viscosity and can be compressible), Bernoulli's principle is an approximation. The full, glorious, and notoriously difficult-to-solve equations that describe the motion of fluid substances are the Navier-Stokes equations. These are a set of coupled, non-linear partial differential equations derived from the conservation of:

- Mass (Continuity Equation): What goes in must come out (or accumulate).

- Momentum (Newton's Second Law for Fluids): Force equals mass times acceleration, but for a fluid element, considering pressure forces, viscous forces, and external body forces (like gravity).

- Energy (First Law of Thermodynamics for Fluids): Accounting for heat transfer, work done by pressure and viscous forces, and changes in internal energy.

Where:

- is density, is velocity vector, is time.

- is pressure.

- is the deviatoric stress tensor (related to viscosity).

- is gravitational acceleration.

- is specific internal energy (energy per unit mass).

- is the heat flux vector.

These equations are the heart of fluid dynamics, used to model everything from weather patterns and ocean currents to airflow over airplane wings and blood flow in arteries. However, their complexity means they often require powerful computers and numerical methods (Computational Fluid Dynamics - CFD) to solve for all but the simplest cases. Finding a general smooth solution to the Navier-Stokes equations is one of the Clay Mathematics Institute's Millennium Prize Problems!

Key Takeaways: Your Fluid Dynamics Cheat Sheet!

What a splash that was! From the simple push of water pressure to the complex swirls of turbulence, fluids are full of fascinating physics. Here are the main currents of thought to carry away:

- Pressure Points: Fluid pressure () increases with depth. Pascal's Law tells us pressure in a confined fluid transmits equally, allowing force multiplication (hydraulic systems).

- Float On! Archimedes' Principle explains buoyancy – an object in a fluid experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces. Density is destiny!

- Skin Deep: Surface tension () creates a "skin" on liquids due to intermolecular forces, leading to droplets, bubbles, and capillary action ().

- Sticky Stuff: Viscosity () is a fluid's resistance to flow (). It leads to drag (Stokes' Law: ) and determines terminal velocity. The Reynolds number () predicts if flow is smooth (laminar) or chaotic (turbulent).

- Bernoulli's Ballet: For ideal fluids, where velocity is high, pressure is low (). This explains airplane lift and Venturi devices.

- The Big Kahunas (Navier-Stokes): These complex equations are the ultimate description of fluid motion, incorporating mass, momentum (including viscous effects), and energy conservation. They're tough to solve but incredibly powerful.

Fluids are truly a symphony of forces and flows, shaping our planet and enabling countless technologies. So next time you see a river bend or a plane soar, you'll have a deeper appreciation for the elegant physics making it all happen! Keep flowing with curiosity!