Going Quantum - The Standard Model, Fuzzy Fields, and the Quest for a Theory of Everything!

Hey there, cosmic explorers and reality researchers! Ever looked up at the stars, or down at your own hand, and pondered the ultimate question: "What is all this stuff really made of?" Not just atoms, but what are atoms made of? And what holds those bits together? What are the absolute, most fundamental ingredients of our universe, and what are the rules of their game?

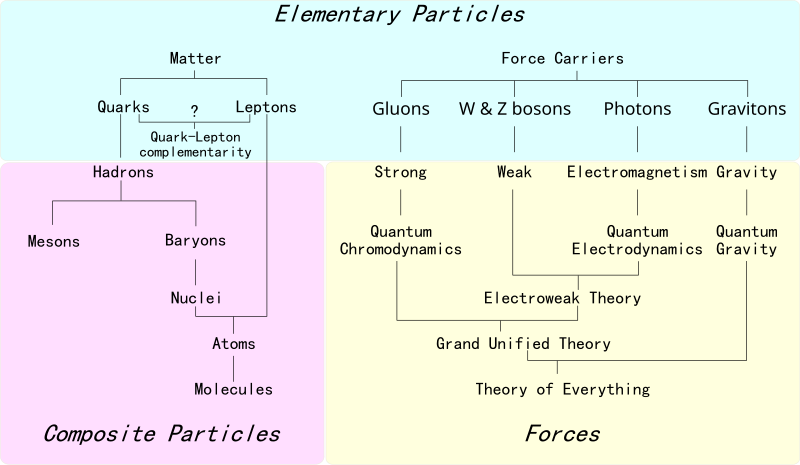

Prepare for a journey to the very edge of known physics, into a realm so small it defies our everyday intuition, yet so powerful it governs everything. We're talking about Particle Physics, and our current best map of this territory is the incredibly successful, yet tantalizingly incomplete, Standard Model. We'll also dip our toes into the mind-bending framework of Quantum Field Theory (QFT), where particles are like ripples on cosmic oceans, and even glance at the frontiers where scientists hunt for an even grander, unified theory.

So, buckle up your quantum seatbelts! We're about to meet a zoo of bizarre particles, explore the forces that make them dance, and ponder the deepest mysteries of existence. It's going to be weird, wonderful, and absolutely fundamental!

The Universe's LEGO Set: The Standard Model of Particle Physics!

The Standard Model of Particle Physics is humanity's most comprehensive and experimentally verified theory of the fundamental building blocks of matter and three of the four known fundamental forces. Think of it as our current "Core Rulebook" for most of what happens in the universe at the smallest scales. It's a triumph of Quantum Field Theory, beautifully combining quantum mechanics and special relativity, and built upon elegant principles like gauge symmetry and renormalizability (don't worry, we'll touch on these!).

The Standard Model describes three fundamental forces (leaving gravity for a later, more complicated party):

- Electromagnetic Force: The good old force responsible for electricity, magnetism, and light itself! It's described by Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) and mediated by the exchange of photons () between charged particles.

- Weak Nuclear Force: This force is a bit more subtle but crucial for processes like radioactive beta decay (how a neutron can turn into a proton) and interactions involving neutrinos. It's described by the Glashow-Weinberg-Salam model (part of the Electroweak Theory) and involves the exchange of heavy W, W, and Z bosons.

- Strong Nuclear Force: The universe's superglue! This incredibly powerful force binds quarks together to form protons and neutrons, and then holds protons and neutrons together in atomic nuclei. It's described by Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) and mediated by the exchange of gluons () between particles that carry "color charge" (quarks).

The Particle Lineup: The matter particles in the Standard Model are all fermions (we'll get to what that means). They come in three "generations" or families, with each generation being a heavier echo of the previous one. Each generation contains two types of quarks and two types of leptons.

And then there's the Higgs boson ()! This special scalar boson is associated with the Higgs field, which permeates all of space. Particles acquire their mass by interacting with this field – the famous Higgs mechanism.

But... It's Not the Final Word! (Limitations & Puzzles) Despite its incredible success, the Standard Model isn't a complete "Theory of Everything." It has some frustrating limitations and leaves us with big questions:

- It doesn't include gravity. Oops!

- The Hierarchy Problem: Why is the Higgs boson so much lighter (its mass around ) than the Planck scale (around ), where quantum gravity effects should become dominant? It seems unnaturally small.

- The Strong CP Problem: Why is a certain parameter () in QCD, which should cause CP violation (a subtle asymmetry between matter/antimatter behavior) in strong interactions, experimentally found to be extremely close to zero?

- Neutrino Masses: The original Standard Model predicted massless neutrinos. But experiments (like neutrino oscillations) have shown they do have tiny masses. How?

- Dark Matter & Dark Energy: Most of the universe isn't made of Standard Model particles! What are these mysterious components?

- Force Unification: Can the three Standard Model forces be unified into a single "Grand Unified Theory" (GUT) at very high energies? And can gravity join that party too?

- Too Many Parameters: The Standard Model has about 19 "free parameters" (like particle masses and coupling constants) that have to be put in by hand from experiments, not derived from first principles. Why these specific values?

So, the Standard Model is an amazing achievement, but it's also a clear signpost pointing towards even deeper physics!

Spinning & Obeying Rules: Spin, Statistics, and Quantum Crowds! ️

Particles in the quantum world have an intrinsic property called spin, which is a form of angular momentum. It's not literally spinning like a top, but it behaves mathematically like it. Spin is quantized, meaning it comes in discrete units of .

The Spin-Statistics Theorem, a profound result in QFT, links a particle's spin to the type of quantum statistics it obeys, which dictates how collections of these particles behave:

-

Fermions: The Antisocial Individualists

- Have half-integer spin (e.g., ) like electrons, protons, neutrons, quarks, and neutrinos.

- Obey Fermi-Dirac statistics.

- Their collective wave function is antisymmetric under the exchange of any two identical fermions:

- This leads directly to the Pauli Exclusion Principle: No two identical fermions can occupy the exact same quantum state simultaneously. They're like cosmic individualists who need their own space! This principle is why atoms have electron shells, giving structure to matter and chemistry as we know it.

-

Bosons: The Social Butterflies

- Have integer spin (e.g., ) like photons, gluons, W/Z bosons, and the Higgs boson.

- Obey Bose-Einstein statistics.

- Their collective wave function is symmetric under the exchange of any two identical bosons:

- Bosons do not obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle. Any number of identical bosons can happily occupy the same quantum state. This leads to cool phenomena like lasers (photons clumping together) and Bose-Einstein condensation.

Mirror Worlds & Anti-Worlds: Parity & Charge Conjugation!

Symmetries are a huge deal in physics. Two important discrete symmetries are:

-

Parity (P): Like Looking in a Quantum Mirror Parity transformation inverts all spatial coordinates: . The parity operator acts on a wavefunction: Where is the intrinsic parity of the particle (a phase factor, usually ). Parity is conserved (the laws of physics look the same in a mirror) by the electromagnetic and strong interactions. However, the weak force spectacularly violates parity conservation! This was a shocking discovery in the 1950s (the Wu experiment).

-

Charge Conjugation (C): Swapping Particles for Antiparticles Charge conjugation transforms a particle into its antiparticle (e.g., electron to positron ), reversing all internal quantum numbers like charge, baryon number, lepton number, etc., but leaving mass, energy, momentum, and spin unchanged. The charge conjugation operator acts on a wavefunction: Where is a phase factor. Like parity, charge conjugation is conserved by EM and strong forces, but also violated by the weak force. However, the combined symmetry CP (Charge Conjugation + Parity) was thought to be conserved for a while... until CP violation was discovered in kaon decays! This tiny CP violation is crucial for explaining why there's more matter than antimatter in the universe.

The Master Recipe: Lagrangian of the Standard Model (A Peek Under the Hood!)

In QFT, the dynamics of particles and their interactions are elegantly encoded in a mathematical function called the Lagrangian density (). The principle of least action then gives us the equations of motion. The Standard Model Lagrangian is a beast, but it's a beautiful beast! It's schematically composed of several key parts:

-

Gauge Sector (): For the Force Carriers! This part describes the kinetic energy and self-interactions of the gauge bosons (photons for U(1), W/Z bosons for SU(2), gluons for SU(3)). For each gauge group, it looks something like: Where is the field strength tensor for the gauge bosons (e.g., for photons ). It contains terms for how the fields propagate and (for non-Abelian groups like SU(2) and SU(3)) how the gauge bosons interact with each other.

-

Fermion Sector (): For Matter Particles & Their Force Interactions! This describes the quarks and leptons and how they interact with the gauge bosons. It includes their kinetic energy and how they "couple" to the forces. Where:

- represents a fermion field (quark or lepton). .

- are the Dirac gamma matrices (we'll meet them soon!).

- is the fermion's mass term (though masses largely come from the Higgs mechanism for fundamental fermions).

- is the covariant derivative. This is the clever bit! It replaces the ordinary derivative and includes terms for the gauge fields, ensuring that the Lagrangian respects the gauge symmetries. For example, for a U(1) gauge field with coupling . This term is what describes how fermions interact with the force carriers.

-

Higgs Sector (): The Magic of Mass Generation! This introduces the Higgs field , a scalar field (spin 0), which is responsible for spontaneous electroweak symmetry breaking and giving mass to the W/Z bosons and, via Yukawa couplings, to the fermions. The crucial part is the Higgs potential : If (the famous "Mexican hat" or "wine bottle" potential), the vacuum state (lowest energy state) is not at . Instead, the Higgs field acquires a non-zero vacuum expectation value (VEV), . This VEV breaks the electroweak symmetry down to , leaving the photon massless but giving masses to the W and Z bosons. The excitations of the Higgs field around this VEV correspond to the Higgs boson.

-

Yukawa Sector (): How Fermions Get Their Specific Masses! The Higgs mechanism gives masses to W/Z bosons directly through its kinetic term interactions. Fermions get their masses by interacting with this Higgs VEV through Yukawa couplings (). Where are left-handed quark doublets, are left-handed lepton doublets, are right-handed singlets, and (and its conjugate ) is the Higgs doublet. When gets its VEV, these terms look like , which is a mass term with . The different Yukawa couplings explain why different fermions have different masses.

Phew! That Lagrangian is the entire Standard Model (minus gravity) in one (very dense) package!

The Particle Zoo: Elementary & Composite Critters!

Let's formally meet the inhabitants of the Standard Model and some of their friends.

(Image: Chart of the Standard Model particles, showing quarks, leptons, gauge bosons, and the Higgs boson.)

(Image: Chart of the Standard Model particles, showing quarks, leptons, gauge bosons, and the Higgs boson.)

Elementary Particles: The Truly Indivisible Ones!

These are the fundamental building blocks, as far as we know.

A. Fermions (Spin-1/2): The Matter Makers!

These are the particles that make up what we typically think of as "matter." They all have spin-1/2. Their dynamics, especially for relativistic spin-1/2 particles, are described by the Dirac Equation.

The Dirac Equation: Giving Fermions Their Quantum Groove! Paul Dirac, trying to combine quantum mechanics and special relativity for electrons, formulated a brilliant equation. Starting with the relativistic energy-momentum relation . The Klein-Gordon equation ( ) arises if you directly quantize this (replace ). But it had issues (like negative probability densities). Dirac wanted an equation linear in both time and space derivatives, like Schrödinger's but relativistic: Where is the momentum operator. For this to be consistent with when squared, the coefficients and couldn't be simple numbers; they had to be matrices (4x4 matrices, it turns out), and had to be a four-component spinor (a type of vector). These matrices must satisfy specific anticommutation relations:

(where is the identity matrix). By defining new matrices and (for ), the Dirac equation can be written more compactly (using natural units for the second form): Here , , and the matrices satisfy the Clifford algebra: where is the Minkowski metric tensor (diag(1,-1,-1,-1) or (-1,1,1,1)). The Dirac equation not only described electrons perfectly but also naturally incorporated their spin and, amazingly, predicted the existence of antiparticles!

Fermions are divided into:

1. Quarks: The Colorful Characters!

Quarks are fundamental but quirky. They have fractional electric charges and experience the strong nuclear force. They carry a quantum number called "color charge" (red, green, blue – just labels, not actual colors!) and are always found "confined" inside composite particles called hadrons, in combinations that are color-neutral ("white"). There are six "flavors" of quarks, arranged in three generations:

- Generation 1: Up (u, charge ), Down (d, charge ) – These make up protons (uud) and neutrons (udd).

- Generation 2: Charm (c, charge ), Strange (s, charge )

- Generation 3: Top (t, charge ), Bottom (b, charge ) – The top quark is incredibly massive!

2. Leptons: The Lightweights (Mostly!) ️

Leptons do not experience the strong force. There are also six flavors of leptons, in three generations:

- Generation 1: Electron (, charge ), Electron Neutrino (, charge 0)

- Generation 2: Muon (, charge – a heavier cousin of the electron), Muon Neutrino (, charge 0)

- Generation 3: Tau (, charge – even heavier!), Tau Neutrino (, charge 0)

Neutrinos are incredibly light and only interact via the weak force (and gravity), making them very hard to detect!

B. Bosons (Integer Spin): The Force Messengers & Mass Giver!

These particles have integer spin (0, 1, 2...). The dynamics of spin-0 scalar bosons (like the Higgs) are described by the Klein-Gordon equation: where is the d'Alembertian operator. For massless spin-1 gauge bosons (like photons, gluons before any mass generation), a common starting Lagrangian is: where is the field strength tensor for a vector potential . The Euler-Lagrange equations give the wave equation (in Lorenz gauge ):

Bosons are divided into:

1. Gauge Bosons (Spin 1): The Force Carriers!

These mediate the fundamental forces:

- Photon (): Carrier of the electromagnetic force. Massless.

- Gluon (): Carrier of the strong force (8 types of gluons). Massless, but confined within hadrons.

- W, W, and Z Bosons: Carriers of the weak force. They are very massive!

(Hypothetical) Gauge Boson (Spin 2):

- Graviton: The hypothesized quantum carrier of the gravitational force. Not yet detected, and not part of the Standard Model.

2. Scalar Boson (Spin 0): The Mass Giver!

- Higgs Boson (): The quantum excitation of the Higgs field. Its discovery in 2012 at CERN was a monumental confirmation of the Higgs mechanism, explaining how fundamental particles acquire mass.

C. Antiparticles: Everyone Has an Evil (or just Opposite) Twin!

The Dirac equation naturally predicted that for every fermion, there's an antiparticle with the same mass and spin, but opposite charge and other quantum numbers (like lepton or baryon number). When a particle meets its antiparticle, they can annihilate each other, releasing energy (e.g., photons)! The charge conjugation operator () transforms a particle's field into its antiparticle's field. For a Dirac spinor , (in one representation), where is a phase and is complex conjugation. anticommutes with in a specific way: .

Quasiparticles: "As If" Particles in Crowded Places!

In complex many-body systems, especially in condensed matter physics, the collective behavior of many interacting particles can sometimes be described as if new, emergent "particles" are moving around. These are quasiparticles. They aren't fundamental, but they are incredibly useful concepts. Examples:

- Phonons: Quantized vibrations in a crystal lattice (like sound wave "particles").

- Magnons: Quantized spin waves in magnetic materials.

- Excitons, polarons, plasmons... a whole zoo of them!

Particle Summary Table (Simplified):

| Category | Particle | Spin | Charge () | Mass (approx.) | Notes / Common Decays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermions (Quarks) | Up (u) | ~2.2 MeV/c² | Stable within hadrons | ||

| Down (d) | ~4.7 MeV/c² | Stable within hadrons | |||

| Charm (c) | ~1.27 GeV/c² | Decays to s or d quarks | |||

| Strange (s) | ~95 MeV/c² | Decays to u quark | |||

| Top (t) | ~173 GeV/c² | Decays to b quark (very quickly!) | |||

| Bottom (b) | ~4.18 GeV/c² | Decays to c or u quarks | |||

| Fermions (Leptons) | Electron () | 0.511 MeV/c² | Stable | ||

| Muon () | 105.7 MeV/c² | ||||

| Tau () | 1.777 GeV/c² | Hadrons or other leptons + neutrinos | |||

| Electron Neutrino () | Very small | Stable (oscillates) | |||

| Muon Neutrino () | Very small | Stable (oscillates) | |||

| Tau Neutrino () | Very small | Stable (oscillates) | |||

| Bosons (Gauge) | Photon () | EM force carrier | |||

| Gluon () | Strong force carrier (8 types) | ||||

| W bosons | 80.4 GeV/c² | Weak force carrier (charged current) | |||

| Z boson | 91.2 GeV/c² | Weak force carrier (neutral current) | |||

| Bosons (Scalar) | Higgs boson () | ~125 GeV/c² | Excitation of Higgs field (gives mass) |

(Note: Quark masses are effective masses, as they are not observed free. Neutrino masses are tiny but non-zero. Many particle decay modes exist; only examples are given.)

Composite Particles: Built from Quarks! (Hadrons)

Elementary quarks are never found alone due to color confinement. They are always bound together by the strong force (via gluons) to form composite particles called hadrons. Hadrons must be "color neutral" or "white."

-

Quantum Numbers: Hadrons (and elementary particles) are characterized by various conserved (or nearly conserved) quantum numbers like: Electric Charge (), Baryon Number (), Lepton Number (), Strangeness (), Charm (), Bottomness (), Topness (), Isospin ( and ). These numbers help us track what's allowed in particle interactions and decays.

-

Baryons (Heavyweights): Made of Three Quarks (qqq)

- Examples: Proton (p) = uud; Neutron (n) = udd.

- Baryons are fermions (half-integer spin).

- The overall wave function of a baryon (space spin flavor color) must be antisymmetric under exchange of identical quarks. The color part of the wave function for a color-singlet baryon is totally antisymmetric: (where are color indices like red, green, blue, and is the Levi-Civita symbol). This antisymmetry in color allows the rest of the wave function (space, spin, flavor) to be symmetric for ground state baryons like protons and neutrons, consistent with the quark model.

-

Mesons (Middleweights): Made of a Quark-Antiquark Pair (q)

- Examples: Pions ( = u, = d, = combination of u and d), Kaons (contain strange quarks).

- Mesons are bosons (integer spin).

- The color wave function of a meson is a color-anticolor pair that forms a color singlet, e.g., .

-

Particle Decays: When Particles Transform! Many composite (and some elementary, like muons) particles are unstable and decay into lighter particles. The weak force is often the culprit behind these transformations. Example: A free neutron decays into a proton, an electron, and an electron antineutrino:

(Image: Feynman diagram showing a neutron decaying into a proton, electron, and antineutrino via a W boson.)

The rate of decay () is given by Fermi's Golden Rule (a result from time-dependent perturbation theory in quantum mechanics):

Where:

(Image: Feynman diagram showing a neutron decaying into a proton, electron, and antineutrino via a W boson.)

The rate of decay () is given by Fermi's Golden Rule (a result from time-dependent perturbation theory in quantum mechanics):

Where:- is the matrix element (or amplitude) for the transition from initial state to final state , calculated from the interaction Hamiltonian.

- is the density of final states (phase space factor).

The Cosmic Glue & More: Particle Interactions & Forces!

The interactions between all these particles are governed by the fundamental forces. We've met three of them in the Standard Model. Gravity is the fourth, currently outside it.

(Image: Overview of Standard Model particles and fundamental forces.)

(Image: Overview of Standard Model particles and fundamental forces.)

| Force | Relative Strength | Range (m) | Mediator(s) | Acts on | Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | (hadron size) | Gluons (8 types) | Quarks, Gluons (color charge) | Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) | |

| Electromagnetic | () | Photon () | Electrically Charged Particles | Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) | |

| Weak | W, W, Z bosons | Quarks, Leptons (flavor) | Electroweak Theory | ||

| Gravitational | Graviton (hypothetical) | All particles with Mass-Energy | General Relativity (classical) |

(Strengths are very approximate and depend on energy scale).

Deep Dive: The Strong Force & Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD)!

The strong force is the Hulk of the fundamental forces at short distances. It's responsible for:

- Binding quarks together to form hadrons (protons, neutrons, etc.).

- The residual strong force binding protons and neutrons together in atomic nuclei.

Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) is the theory of the strong force. It's a non-Abelian gauge theory with SU(3) color symmetry.

- Color Charge: Quarks carry one of three "colors" (red, green, blue) and antiquarks carry "anticolors." These are just labels for the quantum charge of the strong force, not actual visual colors!

- Gluons: The force carriers are 8 types of gluons. Gluons themselves carry color charge (a combination of color and anticolor), which means gluons can interact with other gluons! This makes QCD mathematically very complex, especially at low energies.

- QCD Lagrangian: Where is the gluon field strength tensor (includes gluon self-interaction terms), is the covariant derivative coupling quarks to gluons (with the strong coupling constant and the SU(3) generators).

Key Features of QCD:

- Color Confinement: Only color-neutral ("white") objects can exist as free particles. This means individual quarks and gluons are never observed in isolation; they are permanently confined within hadrons (baryons qqq, mesons q). If you try to pull quarks apart, the energy in the gluon field between them increases until it's energetically cheaper to create new quark-antiquark pairs from the vacuum, forming new hadrons!

- Asymptotic Freedom: The strong coupling "constant" (or ) actually decreases at high energies (short distances). So, quarks and gluons inside a hadron behave almost like free particles when they are very close together. At low energies (larger distances), the coupling becomes very strong, leading to confinement.

- Lattice QCD: Because QCD is so hard to solve analytically at low energies (it's non-perturbative), physicists use powerful computers to simulate it on a discrete spacetime lattice. This has been very successful in calculating hadron masses and other properties.

- Chiral Symmetry Breaking: In the limit of massless quarks, QCD has an approximate "chiral symmetry" related to the left- and right-handedness of quarks. This symmetry is spontaneously broken by the QCD vacuum, which gives rise to a "quark condensate" () and is responsible for the bulk of the mass of hadrons like protons and neutrons (the quark masses themselves contribute only a small fraction!). It also explains why pions are surprisingly light (they are approximate Goldstone bosons of this broken symmetry).

- The Quark Model: While QCD is the fundamental theory, the simpler quark model (classifying hadrons by their constituent quarks: , etc.) is still incredibly useful for understanding the hadron spectrum and their properties.

Deep Dive: The Weak Force & Electroweak Theory!

The weak nuclear force is responsible for some of the most transformative processes in particle physics, like:

- Radioactive beta decay ().

- Nuclear fusion in the Sun (e.g., within a nucleus, or ).

- Interactions of neutrinos.

It's "weak" because its force carriers (W and Z bosons) are very massive (), making its range extremely short ( m). A key feature is that it can change quark and lepton flavors (e.g., a down quark changing into an up quark in beta decay). It also famously violates parity (P) and charge-conjugation (C) symmetries, and even the combined CP symmetry (though to a small extent).

Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) as a Prelude:

QED is the quantum theory of electromagnetism. It's an Abelian gauge theory based on U(1) symmetry. Where (photon field strength) and (covariant derivative coupling charge to photon ). QED is incredibly precise and well-tested.

Fermi's Theory of Weak Interactions (Low Energy Approximation):

Enrico Fermi proposed an early effective theory for beta decay as a point-like, four-fermion interaction (before W/Z bosons were known). For example, muon decay could be described by a term like: Where is the Fermi constant, and incorporates the V-A (vector minus axial-vector) structure that accounts for parity violation.

Electroweak Unification: Merging EM and Weak!

Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg showed that the electromagnetic and weak forces are actually different aspects of a single, unified electroweak force, described by a gauge theory based on the symmetry group SU(2) U(1).

- SU(2): Acts only on left-handed fermions (a key source of parity violation). Associated with three gauge bosons ().

- U(1): Acts on both left- and right-handed fermions (related to "weak hypercharge" ). Associated with one gauge boson ().

The Lagrangian looks like: Initially, all these gauge bosons (and fermions) are massless to preserve the symmetry.

Higgs Mechanism & Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking (SSB): The Mass Miracle!

To give masses to the W/Z bosons (and eventually fermions) while keeping the theory consistent, the Higgs mechanism is invoked. A complex scalar Higgs field (an SU(2) doublet) is introduced with a specific "Mexican hat" potential: If and , the minimum energy state (the vacuum) is not at . The Higgs field acquires a non-zero vacuum expectation value (VEV), . This VEV "spontaneously breaks" the electroweak symmetry down to (the symmetry of electromagnetism).

- Three of the four components of the Higgs doublet are "eaten" by three of the gauge bosons, becoming their longitudinal components and giving them mass. These massive bosons are the W, W, and Z bosons.

- is a mixture of and .

- One gauge boson, the photon (), remains massless. It's a different mixture of and , corresponding to the unbroken symmetry.

- The remaining component of the Higgs field manifests as a physical particle: the Higgs boson ().

Fermions get their mass through Yukawa couplings to this Higgs field, as mentioned earlier.

Neutrino Oscillations: Ghostly Shape-Shifters!

Neutrinos are produced in weak interactions in one of three "flavors": electron neutrino (), muon neutrino (), or tau neutrino (). For a long time, they were thought to be massless. However, experiments have shown that neutrinos can spontaneously change (oscillate) from one flavor to another as they travel. This quantum mechanical phenomenon is only possible if neutrinos have different, non-zero masses, and if their flavor states are mixtures of mass states. This is a big deal because it's physics beyond the original Standard Model (which had massless neutrinos).

The Grand Framework: Quantum Field Theory (QFT) – Where Particles are Field Ripples!

QFT is the fundamental language of modern particle physics. It merges quantum mechanics with special relativity and describes elementary particles not as tiny billiard balls, but as excitations (quanta) of underlying quantum fields that permeate all of spacetime.

- An electron is an excitation of the "electron field."

- A photon is an excitation of the "electromagnetic field."

And so on for all fundamental particles. Interactions between particles are described as interactions between their respective fields.

Key Elements of QFT:

-

Quantum Fields: The fundamental entities are fields (operators at each spacetime point) that can create and annihilate particles.

-

Lagrangian Formalism: The dynamics of these fields are governed by a Lagrangian density (). The Principle of Least Action applied to this Lagrangian (integrated over spacetime to get the action ) yields the field equations (equations of motion). The Euler-Lagrange equation for a field is: The Lagrangian encodes the physics.

-

Symmetries: Symmetries of the Lagrangian are paramount. Noether's Theorem states that every continuous symmetry of the Lagrangian corresponds to a conserved quantity (e.g., time translation symmetry energy conservation; space translation momentum conservation; U(1) gauge symmetry in QED charge conservation).

- Lorentz & Poincaré Symmetry: Physical laws are the same for all inertial observers (Lorentz boosts, rotations) and invariant under spacetime translations (Poincaré).

- Gauge Symmetry: Local phase transformations of fields leave the Lagrangian invariant, but require the introduction of gauge fields (force carriers) and define the interactions.

-

Renormalization: Taming the Infinities! When calculating quantities in QFT (like scattering amplitudes) using perturbation theory (Feynman diagrams), one often encounters infinite results from loop diagrams (integrals over all possible virtual particle momenta). Renormalization is a systematic procedure to handle these infinities.

- Regularization: Temporarily make the integrals finite, e.g., by introducing an ultraviolet momentum cutoff ().

- Renormalization: Absorb the divergent parts (which depend on ) into a redefinition of the "bare" parameters of the Lagrangian (masses, coupling constants, field normalizations), leaving finite, physically measurable "renormalized" parameters. The infinities are swept under the rug by relating them to unobservable bare quantities. Divergent term = Finite physical part + Counterterm (which cancels the divergent part when combined with bare parameters).

- Running Coupling Constants: The "strength" of an interaction (its coupling constant, like or ) is not actually constant but changes with the energy scale () at which the interaction is probed. This is due to quantum loop effects (virtual particle screening/anti-screening). For QED, the effective charge increases at higher energies. For QCD, it decreases (asymptotic freedom). Example for QED: . The formula: relates running coupling to a bare coupling at cutoff .

-

Scattering Amplitudes & Feynman Diagrams: Predicting What Happens When Particles Collide! Particle colliders smash particles together at high energies. QFT allows us to calculate the probabilities of various outcomes (scattering processes, particle creation).

- The S-matrix (scattering matrix) connects initial states to final states . . In perturbation theory (for weak couplings), can be expanded using the Dyson series: (where is the time-ordering operator, is the interaction part of the Hamiltonian).

- Feynman Diagrams: Richard Feynman invented a brilliant pictorial way to organize and calculate the terms in this perturbative expansion. Each diagram represents a specific quantum process:

- Lines: Particles (external lines are real, internal lines are virtual/propagators).

- Vertices: Interactions (where lines meet, strength given by coupling constants).

- The cross-section () (effective area for interaction, related to probability) is proportional to divided by incident flux and summed/integrated over final state phase space.

The Ultimate Quest: A Unified Theory of Physics (The "Theory of Everything"?) ️

The Standard Model is awesome, but it's not the end of the story. Physicists dream of an even more fundamental theory that can:

- Unify all four forces, including gravity.

- Explain the values of the fundamental constants.

- Solve the Standard Model's puzzles (hierarchy, dark matter, etc.).

Current approaches to quantizing gravity (making it compatible with quantum mechanics) face huge challenges, as General Relativity is non-renormalizable in the usual QFT sense. Here are some leading ideas "Beyond the Standard Model":

- Grand Unified Theories (GUTs): Aim to unify the Strong, Weak, and Electromagnetic forces into a single force with a larger gauge group (e.g., SU(5), SO(10)) that is spontaneously broken at very high energies (the GUT scale, GeV).

- Predictions: Proton decay (not yet observed, setting limits on GUT models), relations between quark and lepton properties, magnetic monopoles.

- Supersymmetry (SUSY): A profound symmetry that relates fermions and bosons. Every Standard Model particle would have a "superpartner" (sparticle) with spin differing by 1/2 (e.g., electron selectron, quark squark, photon photino).

- Potential benefits: Can help solve the hierarchy problem, provides dark matter candidates (like the Lightest Supersymmetric Particle, LSP), can help with gauge coupling unification. No sparticles have been found yet at the LHC, pushing SUSY energy scales higher if it exists.

- String Theory / M-Theory: A radical idea where fundamental entities are not point particles but tiny, vibrating one-dimensional "strings" (or higher-dimensional "branes" in M-theory). Different vibrational modes of the string correspond to different particles.

- Potential: Naturally incorporates gravity (a mode of the closed string corresponds to the graviton), aims to unify all forces and matter.

- Challenges: Requires extra spatial dimensions (e.g., 10 or 11 total spacetime dimensions) that must be "compactified" (curled up very small), leads to a vast "landscape" of possible vacuum states, and lacks direct experimental predictions so far.

- Quantum Gravity (other approaches):

- Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG): Quantizes spacetime itself, leading to a discrete, granular structure of space at the Planck scale ("spin networks" and "spin foams"). It's background-independent.

- Asymptotic Safety, Causal Dynamical Triangulations, etc.

The search for a unified theory is one of the most thrilling and challenging frontiers in science, pushing the boundaries of our imagination and our experimental capabilities!

Key Takeaways: Your Quantum Universe Cheat Sheet!

What a mind-altering trip into the quantum realm! From the well-tested Standard Model to the speculative edges of string theory, here's what to remember about the universe's tiniest bits and biggest rules:

- Standard Model: Our best current theory of elementary particles (quarks & leptons as fermions; photons, W/Z, gluons, Higgs as bosons) and three fundamental forces (EM, Weak, Strong). It's built on Quantum Field Theory and gauge symmetries.

- Particles & Fields: In QFT, particles are excitations of quantum fields. Fermions (spin-1/2) obey Pauli Exclusion; Bosons (integer spin) don't. The Dirac equation describes relativistic fermions and predicted antiparticles.

- Forces & Interactions: Forces are mediated by exchanging gauge bosons. The Standard Model Lagrangian mathematically describes all these particles and their interactions, including the Higgs mechanism which gives particles mass via spontaneous symmetry breaking.

- QCD & Electroweak: Strong force (QCD) binds quarks via gluons (color charge, confinement, asymptotic freedom). Electroweak theory unifies EM and Weak forces.

- QFT Essentials: Lagrangians encode dynamics. Symmetries lead to conservation laws. Renormalization tames infinities. Feynman diagrams calculate interaction probabilities (scattering amplitudes).

- Beyond the Standard Model: The SM is incomplete (no gravity, dark matter/energy, etc.). Physicists are exploring GUTs, Supersymmetry, String Theory, and various approaches to Quantum Gravity to find a more fundamental "Theory of Everything."

Particle physics is a testament to human curiosity, revealing a universe far stranger and more wonderful than we could have ever imagined from our everyday experience. The quest to understand its deepest secrets continues! What quantum mystery boggles your mind the most?